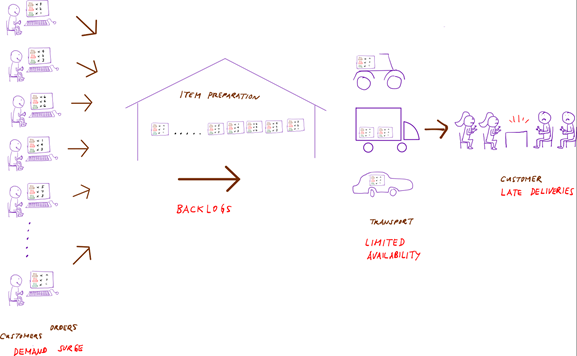

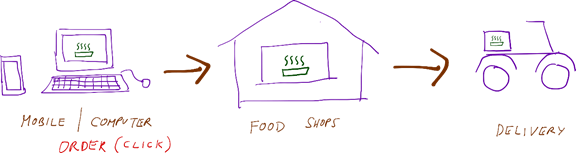

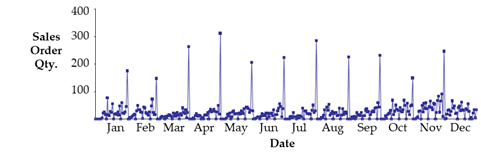

I ordered a box of latex gloves from a 3rd party seller on a popular e-commerce website. The seller confirmed my order by email and after 24 hours, the order status on the website was that the box of gloves was being prepared for shipment. One week later, the order status said it was at a “logistics facility.” Two weeks later, the order status was the item was out of stock, the seller will be unable to ship, and my order was cancelled.

I ordered a box of the very same brand of latex gloves from another seller and I received it within three (3) days. I was annoyed I wasted two weeks waiting for the first one that never came.

Shouldn’t sellers check first if they have stocks physically available on hand before they confirm a customer’s order? Is it not common sense not to sell something one doesn’t have on hand?

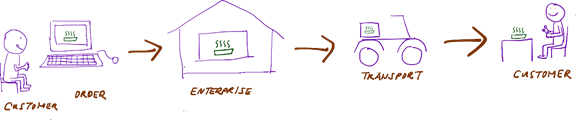

Sounds like yes but in the real world, no. Many enterprises sell items even if they don’t have them on stock. They count on their operations teams to either produce or procure the items and have them available as promised by the time customer wants them.

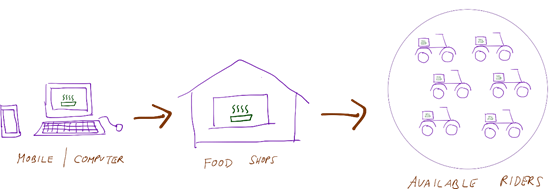

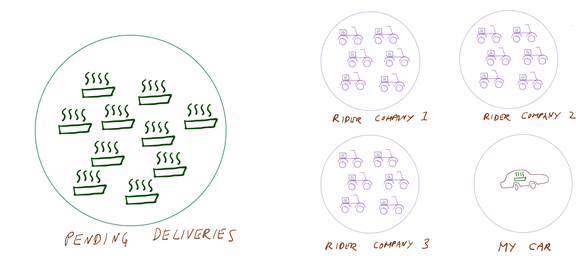

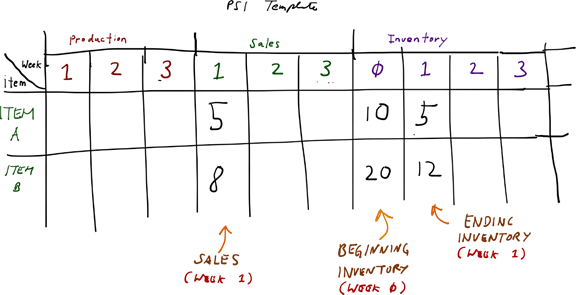

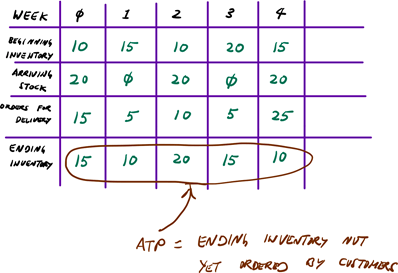

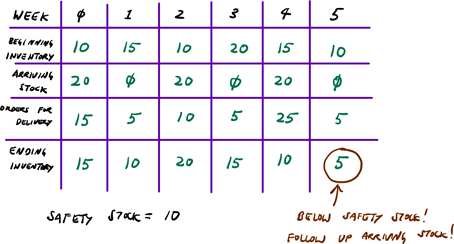

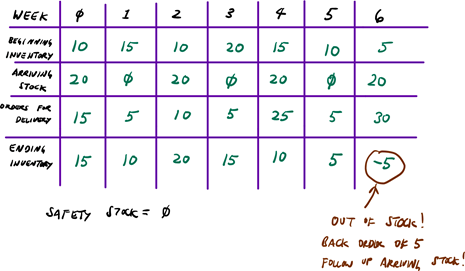

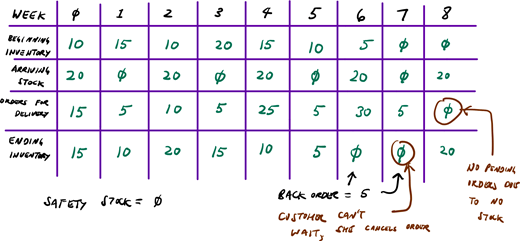

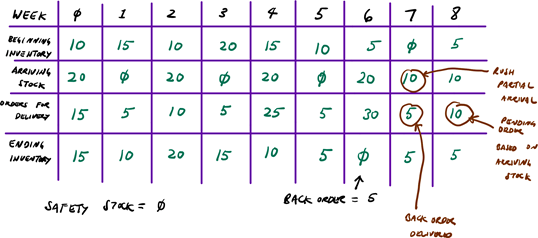

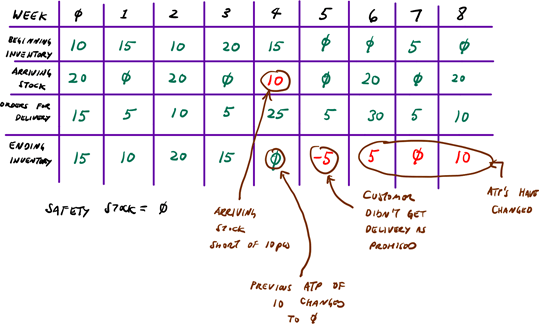

Available-to-promise (ATP) is an inherent element in supply chain management. It is how much of an item an enterprise will have on inventory for customers to buy, adding in what supply is arriving and deducting what’s already reserved for other customers.

ATP = On Hand + Arriving Supply – Reserved for Pending Orders

Enterprise owners count on the ATP to communicate to customers as to how much and when items would be on stock for selling.

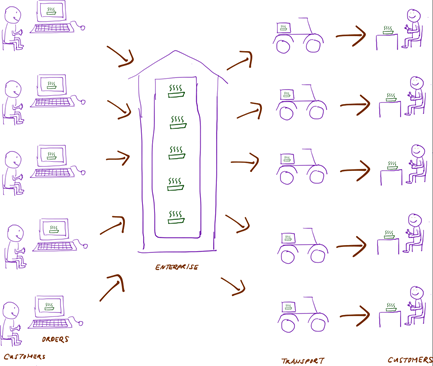

For items that are make-to-stock, enterprises typically make sure they always have enough items on hand at any time for customers to buy. Supply chain managers would set safety stocks to buffer for unexpected demand.

If, however, enterprises are selling expensive stuff like precious metals, are in the business of shipping thousands of items like automotive parts, or are marketing products with short shelf lives, managers would not keep too much on hand to avoid tying up capital in inventory. Managers wouldn’t keep any safety stock and would rely on scheduled arrivals when committing ATP to customers.

Customers expect enterprises to deliver their items on-time and complete as promised. How well an enterprise keeps its promises is a criterion for success. ATP is therefore important. It’s one thing both the customer and enterprise care about. Delivering as promised ranks right up there with quality, cost, and service.

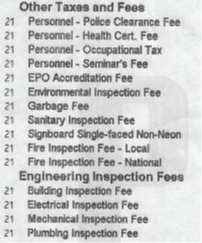

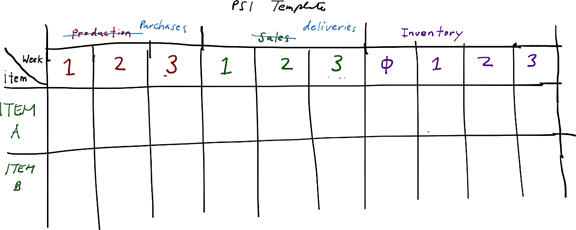

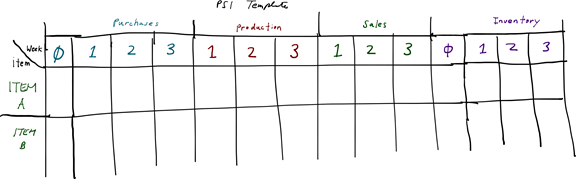

Supply chain executives should strive for the following when it comes to planning ATP:

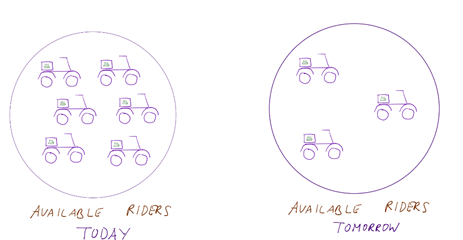

Never Zero, At Least Not Often

No one likes to be told an item is out of stock. Mothers don’t like it when their favourite brand of diapers for their babies are not on the drugstore’s shelf. They would buy another brand if they come back in a week and there’s still no stock.

Short Lead Times

Customers will cancel their orders if a shop says the items they want won’t be ready for several days. We humans have thresholds when it comes to patience. We won’t wait too long. Enterprises who can quickly churn products for customers gain competitive advantage.

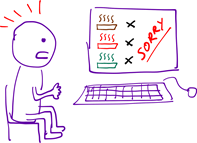

It Doesn’t Change at the Last Minute

Nothing is worse than breaking a promise. Few things are as frustrating as when a shop tells us that there will be a delay in the item that was supposed to be delivered today. It feels even more frustrating if we had already paid for the item. Frustrated customers won’t be comforted with apologies or refunds. Customer satisfaction comes when deliveries happen, not when they don’t.

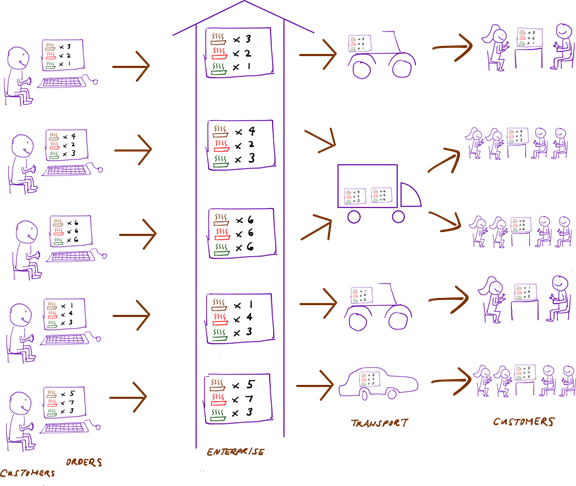

One Person in Charge

There should only be one person in charge of ATP. Not the planner. Not the logistics officer. Nor the plant manager. Not anyone else but the supply chain executive, the one who oversees all the operations for the fulfilment of customer orders.

That means the delivery of items to the customers’ doorsteps, the making of the items, the marshalling of resources to make and deliver the items, and the shipping of the items. In short, the enterprise’s supply chain.

Enterprises, therefore, should have a chief supply chain officer who’d be in charge of making available what is promised.

Having two or more persons handle supply chain operations or delegating the accountability of ATP to middle managers are common mistakes that lead to items that won’t be there as committed. Having more than one person in charge of the fulfilment of customer demand just makes no sense.

It’s like a kitchen with two chefs: one is in charge of buying the ingredients, the other oversees the cooking. Both men would be fighting each other in no time. As the saying goes, “too many chefs spoil the soup.”

Keep It Simple

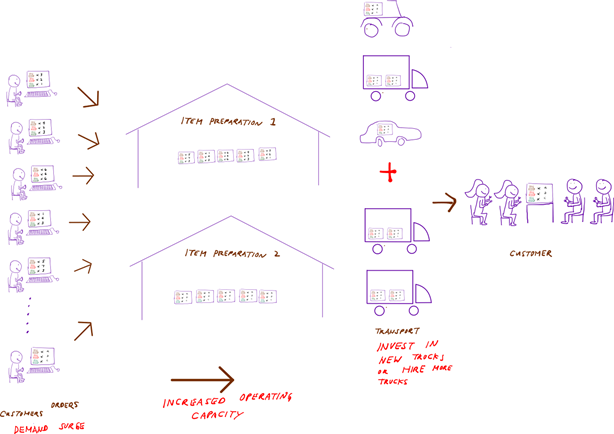

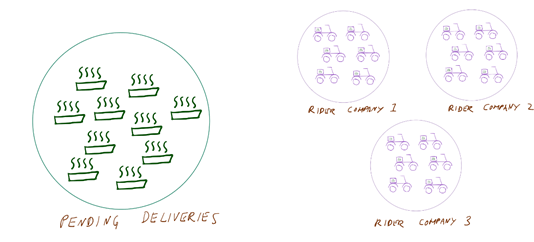

The more complicated an enterprise’s operations, the harder it is to keep promises.

Thousands of items, multiple steps, shared production lines, and conflicting policies & targets are examples in which management becomes muddled as items weave through supply chain operations to get to customers.

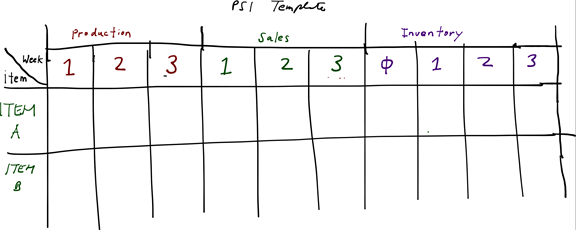

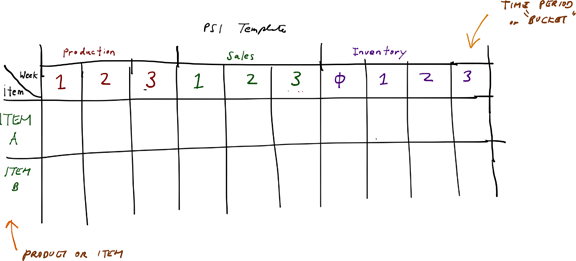

The advice is to keep it simple and use common sense. Schedule milestones operation by operation to know how much can be committed at the end of the supply chain. Deliver with smaller trucks or send single items through couriers. Keep few stocks but set automatic re-order points for items that don’t move as much (e.g. spare parts). Don’t keep stock of items that are make-to-order (e.g. tailored clothes).

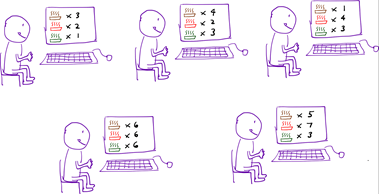

Nothing Wrong with Being Conservative

There’s nothing wrong with applying an allowance to an ATP. If the schedule says an item will be ready in four (4) weeks, commit to five (5) when the customer asks. Adding an extra week would allow for unforeseen events such as if a supplier falls short in delivering needed materials.

No farmer can surely know how many fruits he will pick today. A fisherman wouldn’t know exactly how many fish he will catch tomorrow. But experience will allow either to provide safe estimates. The same is true for ATP. We never really know exactly how much items will be available but we’d be more confident with conservative numbers, just as long as it doesn’t lead to over-padding or over-commitment.

Enterprises and customers put a lot of weight in what is available to promise. Customers rely on enterprises keeping their word. Enterprises depend on their operations to have items ready when needed.

Enterprises should avoid promising nothing to make available and when they do, shouldn’t make last-minute changes. There should be only person in charge and he or she should be the one who oversees the operations in making ATPs realities. Planning ATPs should be as simple as possible and can be made with some conservatism. We should not over-commit or pad too much.

We make promises we can keep. People value us for how we act based on our words. It becomes not only a mark for success but also a way forward to mutually beneficial relationships.