The process of customer order creation and fulfilment is a core task of many enterprises.

An order creation & fulfilment process in a business-to-business (B2B) relationship typically consists of the following steps:

- Propose: Enterprise via marketing & sales presents product or service (i.e. item) to customers.

- Request: Customer expresses interest

- Quote: Enterprise provides prices, terms, & availability

- Order: Customer orders items

- Validate: Enterprise sales accounting checks legitimacy of customer & order (e.g. credit line, completeness of data).

- Enter: Enterprise sales accepts order & inputs it as a pending order

- Allocate: Enterprise logistics reserves available items to pending order

- Pick: Enterprise logistics physically picks items from inventory & stages them for shipment

- Delivery: Enterprise logistics books & dispatches transport of items to customer

- Post-Sales Services: Enterprise via sales & logistics acts on any customer feedback or complaint (e.g., customer returns items, enterprise replaces or fixes items covered by warranty)

Enterprises who sell directly to end-users, that is business-to-consumer (B2C, e.g., supermarkets, e-commerce, restaurants) typically have a simpler process:

- Advertise: Enterprise displays items for sale (e.g. on shelf, on screen, menu)

- Inquire: Customers ask about items (e.g. price, features, available variants)

- Pick: Customers choose items (e.g. place in shopping cart)

- Check-Out: Customers commits to buy (e.g. makes payment); enterprise confirms order & payment

- Obtain: Enterprise delivers items; customer receives & accepts items

- Post-Sales Services: Enterprise via sales & logistics acts on any customer feedback or complaint (e.g., customer returns items, enterprise replaces or fixes items covered by warranty)

Enterprises who offer services, such as what we see in the travel industry, would follow an order creation & fulfilment process like the following:

- Advertise: Enterprise displays services for sale (e.g. flight schedules, hotel promotions)

- Inquire: Customers ask about services (e.g. price, terms, available seats or rooms)

- Book: Customers reserve for services (e.g., seats, rooms, tours, tickets)

- Pay: Customers pay (depending on terms)

- Register: Customers show up to obtain services (e.g., flight or hotel check-ins)

- Experience: Enterprises provide services (e.g., in-flight amenities, transportation, lodging)

- Post–Services: Enterprises refund or rebate services for complaints; enterprises reward clients or customers for patronage

The common thread for any order creation & fulfilment process in most enterprises is:

- Inquire

- Order

- Allocate

- Deliver

- Pay

- Post-Sales Services

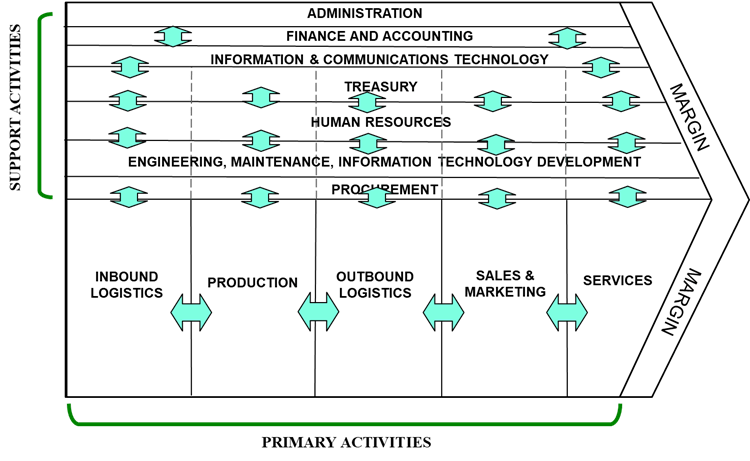

In many of our enterprises, we share these steps among functions. Sales & Marketing, for instance, would handle inquiries, orders, & post-sales, while Operations would take care of allocation & delivery. Finance and Sales would handle payments & collections (which often cause confusion in who’s accountable).

The purpose of any order creation & fulfilment process is to support the enterprise’s objectives, such as:

- Meet targeted sales or revenues

- Attain competitive advantage

- Expand market share

- Build reputation & influence

An order creation & fulfilment process has three typical (3) tactical aims:

- Entice customers to order

- Deliver items completely and on-time

- Pursue payments

We depend on several factors for an order creation & fulfilment process to succeed. Examples of such factors include:

- Inventories (e.g., items on stock, available seats)

- Assets (e.g., manufacturing capacities, available transport, storage/shelf space, uptime & speed of online portals)

- Policies (e.g., terms, rules for order acceptance, credit lines, prerequisite qualifications, less-than-truckload [LTL] allowances, returns & exchanges, inventory policy)

- Methods (e.g., do-it-yourself-checkouts at supermarkets, online ordering, payment options, salesperson calls & visits

- People (e.g., organisational structure, competencies, head count)

We look to several models or tactics to enhance the order creation & fulfilment systems. Examples include:

- Inventory Policies (e.g., minimum stock on-hand, economic order quantity [EOQ], ABC inventories)

- Operations Planning (e.g., Enterprise Resource Planning [ERP], Just-In-Time)

- Demand Forecasting (e.g., trending demand, seasonal factoring, bottoms-up sales forecasting)

- Manufacturing & Logistics Models (e.g., multiple workstations, cellular manufacturing, job shops, hub & spoke networks)

- Workplace Systems (e.g., job specialisation & rotation, incentives & quotas, work teams & quality circles).

Order creation & fulfilment is not a straightforward process, as some of us may think. For many enterprises, it is a complicated sequence of steps, in which its performance is dependent on factors such as what were mentioned above (available inventory, asset capabilities, policies, methods & systems in place, & organisational competencies).

We determine how our order creation & fulfilment processes perform. That is, we establish the policies, systems, & structures.

The process differs from one enterprise to the next, contingent on the type of product or service we market & sell, the strategy we lead, and the rules we set.

Some enterprise executives try to improve order creation & fulfilment via brute force, such as mandating criteria & standards everyone in the organisation must comply with. Examples:

- Maximum Inventories (e.g,, total inventories must not exceed 30 days of sales)

- Acceptable Service Level (e.g., order must be delivered complete in three [3] days)

- Sales Targets (e.g., monthly shipment volume goal)

Most mandates fail because they’re frequently done without any assessment or change in existing structures or systems. Items run out (or wrong items are stocked), deliveries are rushed without regard to quality of service, and people get stressed & burned out. Like a rubber band, the systems underlying the process reverts back to its past state. Executives & customers fret.

Order creation & fulfilment is a process that underlie the two (2) basic tasks of our enterprises:

- Create demand

- Fulfil it

It is a good starting point to study for improvements in our supply chains.