Supply chains had become popular in the 2020’s, thanks greatly to the era of the coronavirus pandemic when our world experienced major economic disruptions in transportation, production, and deliveries. Because of aggravations such as missed deliveries, shortages, and overstocked inventories, we pledged we’d do better in managing our supply chains.

But we hadn’t done much better. Supply chains, despite our recognition of its importance, continue to challenge us. We face disruptions in sourcing critical materials, climbing prices, and uncertainties in demand. We haven’t come to grips in improving, if not just controlling, our supply chains.

Some of the reasons why we haven’t been that much successful with supply chains lie in their characteristics. Supply chains are models. They represent interdependent relationships between enterprises in which their overall common purpose is to add and reap value from the merchandise & services which flow through and between organisations & operations. Hence, working to optimise supply chains require us to understand what they are.

Number 1: Supply Chains are Complicated

We hardly will find a supply chain we could call simple.

Supply chains are not singular flows limited to three (3) activities, i.e., buy-make-deliver. Supply chains are made up of multitudes of activities. Each activity interacts directly or indirectly with the others in which the performance of one affects the results of another and the supply chain in whole.

Supply chains also don’t go in one direction. They diverge and converge. Iron ore from a mine, for example, go to mills which convert them to all kinds of steel products such as bars, ingots, or plates. These steel products, in turn, become raw materials for all kinds of items like structural beams, cars, appliances, & furniture. Some scrap metals from the factories return to steel mills for reprocessing. The steel supply chain involves countless vendors, 3rd party providers, & customers, aside from the multiple items it makes available.

In supply chains, we buy not only materials to convert to finished products but also purchase spare parts for our machines. We build multiple factories or outsource production to 3rd parties and set up distribution centres. We book with brokers to import & export items and at the same time dispatch both vehicles we own or hire to deliver items to buyers.

Any flow chart of any supply chain would show arrows moving to and from activities. It gets even more complex when we map activities of items which share operations with others. Operations for one day may not be the same as the next, depending on what items we’re churning out.

Each supply chain activity is either value-adding (e.g. conversion of raw materials to products, quality control inspection & passing of inbound imported items) or non-value-adding (e.g., items waiting for loading on a vessel, retrieval of rejected merchandise from customers, shuttling empty passenger planes between airports).

As each of us have differing views of value, we may not entirely agree with one another on what operation adds value and which does not. That makes mapping supply chains and pinpointing what activity to prioritise for managing more complicated.

We can rely on our superiors to decide what adds value and what does not. But it’s not that straightforward, because of the next characteristic.

Number 2: Supply Chains Are Beyond the Scope of Any One Enterprise.

No one enterprise rules over an entire supply chain. There will always be an ingredient, material, or service which we would need that would come from outside of our scope of management. Our enterprises can be as simple as a farm where we live off from harvesting our own crops and from tending to our own livestock. We would still need, however, to buy seeds, fertiliser, feeds, nutrients, medicines, supplies, and any other stuff which we can’t make on our own. And the people who sell us this stuff won’t necessarily be under our authority. We’d be negotiating with them to marry our interests with theirs.

We likewise cannot dictate to the customers who buy our crops & livestock, following the example of the farm. We also would need to negotiate for terms & prices favourable for both us and the buyers.

There are conglomerates which vertically integrate their operations, in which they buy stakes in vendors and 3rd party logistics providers to expand their influence over their supply chains. Some corporations insist on exclusive contracts with suppliers and dealers to lock in supply and distribution of their merchandise. But as much as they may dominate a good part of their supply chains, companies, no matter how big, can’t have it all. There would still be some parts of the supply chain they won’t have full control over.

Supply chains require cooperation and synchronisation between their links. Interaction is a constant. Relationships are vital. Collaboration is a must. We may define our own whatever strategy for our own enterprises, but we cannot escape negotiating with firms who are outside our scope of authority but whom we need for supply or delivery. We can’t have our own vision unless other firms in the supply chain share common ground with us.

And if you think it’s easy to share common ground. Consider the next characteristic.

Number 3: Supply Chains are Vast

Many supply chains, if not all, encircle the globe and involve so many enterprises. For whatever we sell or buy, we are connected in some fashion with many industries around the world. The fruits we buy from Korea could have used fertiliser from Canada. China may have assembled our mobile phones together with lithium-ion batteries their local vendors also produced but which the metals for the phone’s circuits may have originally come from South Africa.

Just about all items we buy and sell may have passed through supply chains which passed from international sources and utilised all kinds of transportation (e.g., sea, rail, air).

Hence, most supply chains are global. They are not necessarily centred in one place as much as they are dominated by one or few enterprises. As much as nations & corporations like to have total control, they’d be contending with operations that are far-reaching and consisting of many types of activities.

The vastness of supply chains has prompted us to develop the structures & systems which convey the flows of products & services. This leads us to the next characteristic of supply chains.

Number 4: Supply Chains are Only Strongest at Their Weakest Links

As mentioned in Number 1 above, supply chains aren’t simple singular chains limited to buy-make-deliver activities. Rather, they are complex relationships in which merchandise & services flow to and from multiple activities.

But, however, complicated they are, supply chains are strongest only at their weakest links, that is, they depend on every operation’s performance. Any operation’s results would have an effect on the total supply chain

But wait a minute. If supply chains are complicated and involve so many multiple operations, wouldn’t there be redundancy? Enterprises could easily make up for one link’s subpar performance with other equivalent ones, right? In the event of failure of one link, we can switch suppliers, hire other transport providers, or keep production lines running via standby machines or spare parts, correct? And we can also keep inventories of merchandise to buffer against the unreliable links?

Our mantra is to fulfil demand. When there is demand, such as a customer order, we serve it. Demand, however, is not a steady constant. It swings depending on the instantaneous needs of customers. And demand isn’t really steady, it grows or declines over time.

In our operations, therefore, there will be times we will have more than enough capacity and there will be times we won’t. We may have more than enough trucks, for instance, to deliver our products at the start of the month and won’t have enough to deliver when salespeople submit last-minute orders to pursue quotas at the end of the month. Even if we have the inventories, our operations may not have the immediate capabilities to fulfil the demand at that moment it comes in.

Weak links are like moving targets. Today it may be transportation, tomorrow it would be manufacturing. Demand is a dynamic; it does not remain constant. even if we know how much customers will buy in a month, we wouldn’t know how much they’ll order today. Any one operation may not have the capability to serve the needs this instant.

We second guess where our weak links would be. We boost capacities, source from multiple suppliers, and negotiate contracts with different transportation outfits. But any given day there would be a particular operational link that would be setting the pace of performance of the supply chain, given the demand of that day.

We develop a lot on infrastructure like roads, bridges, railways, shipping lanes, & ports to strengthen our supply chains. We upgrade our manufacturing & logistics facilities and set up transport networks. We invest in information technologies & automation. By doing so, we try to mitigate the weak links in our supply chains.

But we need talented people to ensure what we do to improve our supply chains will succeed. But the talents we need has to fit in with the supply chains they will be engaged with.

Number 5: Every Supply Chain is Unique

We can identify an enterprise by not only its product or service but also by their supply chains.

No two (2) supply chains are alike. No matter how identical two (2) competing items may be, there will always be differences in how they’re made, where their components or ingredients come from, and how we conduct their logistics.

The organisations behind supply chains also would differ. The talents of managers, staff, and technical crews would not be the same from one enterprise to the next. A supply chain would differ from one another as much as individual human beings do.

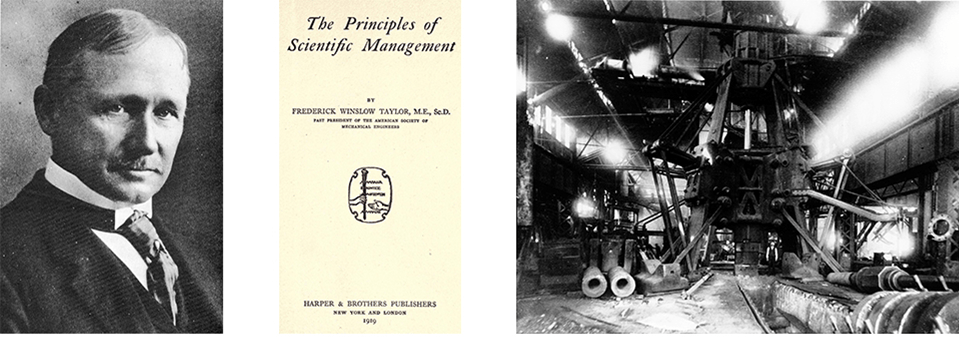

Supply chains rely on the talents and experiences of the organisations which manage it. Vendors, enterprises, and customers play their parts in supply chains; each has a role and not any participant is left out. Outsiders, like contractors & consultants, who don’t have roles in supply chains cannot be expected to be recognised as experts even if they may have their own experiences & insights.

Hiring, therefore, is only a starting point when it comes to bolstering a supply chain’s organisation. Training & organisational development count too, as well as the retention of well-honed talented managers, engineers, operators, & technicians. It’s the wisdom of people who have worked long in their supply chains that would be invaluable to new people.

Consultants & mentors from outside the supply chains can help when it comes to teaching management principles. Engineering education is always a plus. But I believe the best talent comes from those who learn from the guidance of experienced in-house managers & workers.

Supply chains are complicated, go beyond any enterprise’s scope, are vast, are strongest only at their weakest links, and each is unique. These five (5) characteristics are what make supply chains not only not easy to comprehend but also downright challenging.

Because supply chains are made up by our relationships with vendors, customers, & 3rd parties, we must focus on how we deal not only with the links within our enterprises but also with all individuals who add value to the stream of goods & services.

We can’t work on supply chains by our own authority. We can’t dominate them as much as we may gain more influence. We negotiate so we can all collaborate. Never mind if we find it a hard reality that we must work with other people in supply chains.

Any success we attain would be worth it.

About Ellery’s Essays