Since Keith Oliver and a Mr. Van ’t Hoff coined the phrase in the 1980s, supply chain management has evolved from an obscure middle-management responsibility to a high-echelon business priority. Supply chains had become hot topics in executive suites and business school lecture halls. At the same time, operations managers face endless enigmatic problems as external factors from natural disasters to geopolitical events rock global trade.

Supply chains are far more different from what they were in the 1980s but at the same time, they’re not, in some respects.

What did change?

Supply chains have advanced technologically.

Thanks largely to pioneers like Amazon, consumers order many products via e-commerce portals. Warehouse management systems (WMS), artificially intelligent (AI) algorithms & robots assist logistics workers in allocating, picking, loading, and dispatching deliveries.

Supersize containerships, self-driving vehicles, drones, and longer-range energy-efficient aircraft are propelling the transportation of merchandise not only faster and farther but also at greater volumes.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is also enabling enterprises to upgrade not only the automation of their factories but also of their offices. Executives had been aspiring to apply AI in the planning and execution of all supply chain operations.

What didn’t change?

Supply chains are global, but they always have been since civilisations began buying and selling from one another. The ancient Silk Road connected Asian merchants with Europe. Europeans, in turn from the medieval ages, shipped goods by sea to and from the American New World and the Far East. American railroads, at the onset of the 19th century Industrial Revolution, transported products & people from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific. In the 20th century, nations trade globally via the Internet and elaborate transportation networks.

Supply chains had been predominantly dependent on contracts which organisations haggle and hammer out with vendors & customers. At the same time, nation-state governments had taxed & regulated supply chain operations, such as manufacturing and export & import activities.

Executives also had tended to limit supply chain management to operations which they have direct influence over. Even before supply chain management became a buzz-phrase, enterprises already were forecasting demand, processing orders, controlling inventories, planning production & capacities, inspecting & assuring quality, reducing expenses, spending for fixed assets, supporting new product initiatives, and measuring performances.

A good number of business owners, however, continue to treat supply chains as nothing more than logistics or transportation. Manufacturing and purchasing functions have remained outside of supply chain managers’ scopes in many firms.

Worse, some managers have blamed supply chain management for undelivered pending sales orders, product stock shortfalls, customer complaints, runaway costs, and high working capital.

What also hasn’t changed was the perception that computerisation and automation are the best solutions for supply chains. Much of what have been talked about in supply chain social media sites and business articles are how much hope executives, academics, bloggers, and consultants have been putting in on state-of-the-art artificially intelligent (AI) driven information technologies (IT) to drive supply chains to the next level, whatever that would be.

And finally, what has also not changed since Keith Oliver’s time is that supply chains could only be improved via management. Supply chain management is operations management, one of four basic branches of business administration which included sales & marketing, finance, and people. Supply chains are components of the business of operations.

Executives had thought they could improve supply chains via management, they saw themselves as ready experts as per their business acumens. They saw themselves as more than qualified what with their education from business schools and/or from their hands-on experience in their respective industries. Executives had been confident they could manage supply chains via the basic management principles of planning, organising, directing, and controlling.

Managers have gauged supply chains based on assessed capabilities. Hence, to improve supply chains, executives simply needed to hike capabilities. The obvious options would be in tactics such as increasing production capacities, adding more logistics assets such as storage space & handling equipment, and hiring more people.

Managers also leaned toward information technologies to drive supply chain improvements. Executives just needed to invest in IT hardware & software to automate processes and streamline the flow of data & merchandise. Never mind that almost one out of two enterprises have not succeeded in implementing new IT into their business.

Also hardly changed was the bias of executives towards the other branches of business administration, namely sales & marketing, finance, & people (organisational development). Many executives tended to delegate supply chain management to subordinates because they either had no professional experience, or they just didn’t see it as an avenue for personal career development. Supply chain management was a slow-growth career path. Much attention to supply chains in many firms stemmed from crises, such as when materials don’t arrive or customers complained about unserved orders, late deliveries, or off-quality goods. Many executives did not see supply chain management as an equal to strategic planning.

Supply chains had, therefore, gotten stuck. Executives stubbornly held on to the belief that supply chains were no more than internal operations which they by themselves could handle. New attractive technologies like AI & robotics, were the easy answers for improvements; all that was required was capital investment.

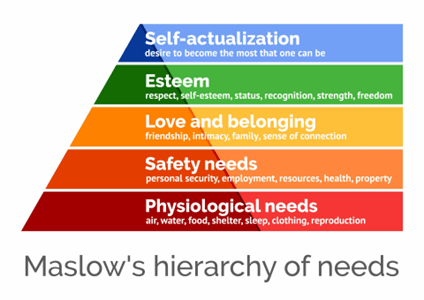

If we want to improve supply chains, we’d need to change how we perceive them:

- Supply chains are not limited to the internal operations of an enterprise; they encompass activities that add value to merchandise & services from the point of their creation to their final usage or consumption.

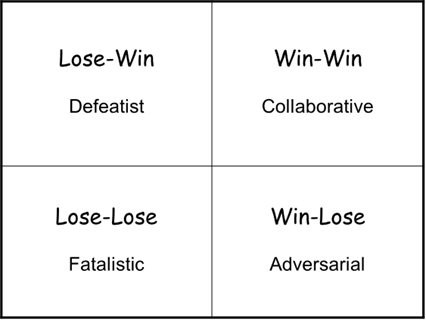

- Supply chains consist of relationships in which their effectiveness & efficiencies rest on the maturities of the partnerships forged between parties.

- Structures & systems underlie the operations of supply chains, and they are where we should focus any improvement, not only in their capabilities, but also in their achievements to meet the strategic priorities of organisations.

It would be quite a tall order for executives to veer from the mindset of meeting their enterprises’ individual priorities to that of nurturing supply chain win-win relationships and building structures & systems beyond the boundaries of their internal operations.

This is not something entirely new. Past civilisations had recognised the need to work with partners such as vendors & customers. Merchants, craftsmen, and shipping owners had always been active in improving methods and workplaces.

What’s different is that we should take in a more holistic approach in dealing with our supply chains. As much as we may continue focusing on minute tasks, we should also be approach supply chains as relationships working together in unison. We should define how every link should perform and how every connection should work together.

It is from there, we can build the supply chains we want, regardless of how different they may be from the ones of today.

Find Ellery