It’s a question I encounter at the end of every seminar:

What Now?

Where do we go from here? How do we start? Where do we start? What do we do?

Most seminars end with people praising the principles learned but then hardly applying them in real life.

Why is it so hard to apply the things we learned which we come to believe are ground-breaking?

Take Lean, for example. The Lean Institute preaches the benefits and practices of bringing Lean Thinking into organisations. The Lean Institute aggressively conducts or sponsors seminars and workshops around the world. The institute has endorsed, if not published, books and articles about Lean from authoritative figures from the business world and academe. Many companies who have implemented Lean testify to the success of Lean.

Yet, many companies who have attended Lean seminars, read Lean books, and listened to speakers endorsing Lean ended up not fully implementing Lean, and if they tried to, many among them failed.

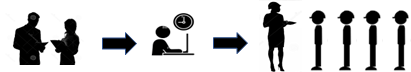

Tim Mclean believes Lean implementation would succeed if there were at least two things present:

Note that the numbering sequence of the two things above starts from #2: Leadership to #1: Goal. Mr. Mclean believes that the success of any Lean implementation most importantly depends on what the goal of the enterprise is. Executives are after all, logically serious about their goals and would focus on them as their agenda of leadership.

However, if we define success in Lean as “achieving our goals” then we can set goals that we as individual leaders can achieve. For example, in the 1990’s I managed a plastic moulding factory. We set ourselves the goal of improving uptime (overall equipment efficiency) and reducing scrap. This was a goal which I, as the plant manager, could lead. My senior management just wanted cost reduction. They did not care how it was achieved. We chose to use a Lean approach, developing the skills of our front-line leaders and driving 5S, visual management, TPM, SMED and problem solving to achieve a 50% reduction in scrap and a 25% increase in OEE. We had “Lean success”, but I can assure you that this plant was nowhere near a Shingo prize!

We can apply the same line of thinking with any principle that enterprise leaders would want to apply in their organisations. To effect change towards a new concept, idea, or system, we must first determine our goal, which is what we want, and cascade this goal to our fellow stakeholders so all of us would own it and commit to it. Implementation via strategic and action planning follows.

It’s our goal as enterprise leaders that determines the direction of our organisations and their priorities. When we go attend a seminar or enrol into a course paid for by our employers, we do so to find out how relevant the principles we learn are to the goals of our organisations.

We can evaluate what we learned and report what we think to our superiors. Consultants and engineers do this a lot but, in the end, it’s up to us as leaders and managers to decide whether to adopt a new principle, concept or idea.