It’s hard to just get started.

It’s hard sometimes to wake myself up in the morning to work out despite the fact that I told myself I will and that I even set the alarm to make sure. And when the alarm sounds, I find myself questioning whether to really go through with it.

I find excuses. My back aches. It’s cloudy and might rain. It’s too cold. It’s maybe better to use the time to work on my business report. Etcetera. Etcetera.

But once I realise that I’d lose that precious time slot I invested for my morning exercise, I decide (sometimes with difficulty) to get up, suit up, and do my workout.

Once I’ve lifted that barbell and start to break a sweat, I find myself feeling good that I had decided to push through with the morning exercise.

It happens a lot of time to us. Just getting started is always the hardest part. But once we’re into it, there is momentum. It becomes easier to finish a job as we get deeper into it.

A journey of a thousand miles indeed begins with the first step. And the first step is always the hardest. Whether it be a simple job or a long trip, we find it often hard just to get started.

This is because a journey’s first step isn’t really that one foot out the door. A first step begins with writing a plan, packing that suitcase, or in my example of my morning work-out, getting out of bed.

For several years, my relatives have talked about travelling to Spain and taking that long hike to the Santiago de Compostela.

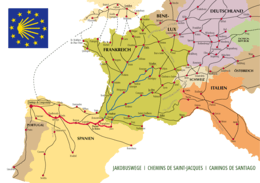

The Santiago de Compostela is a cathedral located in the city named after it. It is the reputed burial site of St. James, one of the Twelve (12) Apostles of Jesus Christ. The Santiago de Compostela has been a famous destination for Catholic pilgrims and tourists especially those who took the Camino de Santiago, the Way of St. James, a network of walking trails that lead to the cathedral.

Many who have taken the walking route found it very much worth it. Plenty of scenery. Fresh air. Good exercise. Staying overnight at inns and sampling the local Spanish Galician cuisine. And finally seeing that majestic cathedral at the end of the trail. The awesome baroque cathedral that takes away the breath of many who see it the first time.

The traditional route favoured by die-hard travellers is the French Way which goes as far as 800 kilometres and would take several days even for the fastest walkers. Tourists usually opt for the much shorter routes although in order to secure a certificate of pilgrimage, one has to at least walk a hundred (100) kilometres.

But as I and relatives have talked about taking the trip. It so far has been just that: talk. We haven’t taken any first step, which isn’t that first footstep on the trail but just getting to making an itinerary, booking a flight, or deciding which of the walking journeys to take.

Whether it be a daily morning work-out, an 800-kilometre hike like the Camino de Santiago, or a job we have to do at work or at home, we don’t get anywhere unless we make that first step. It’s not deciding that we’ll do it. It’s not telling ourselves we will do it. And it isn’t that first footstep or that first lift of a barbell. It’s the execution, the act itself that matters.

It’s getting out of bed, booking that reservation, making that phone call, and finally getting to work that constitute those very first steps to whatever we intend to do.

It’s hard to get started. But we won’t regret it when we do.