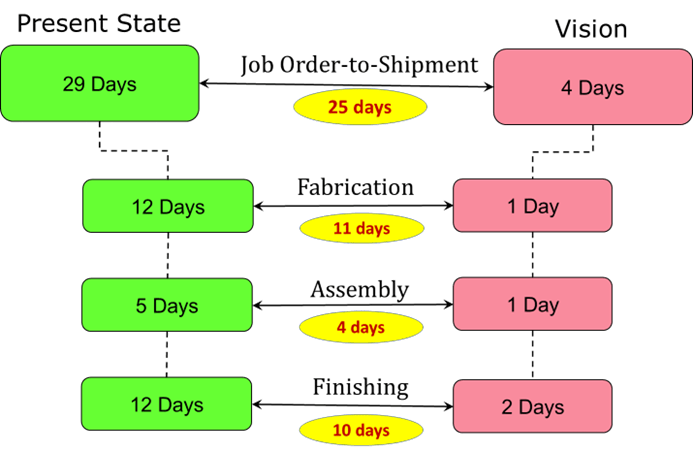

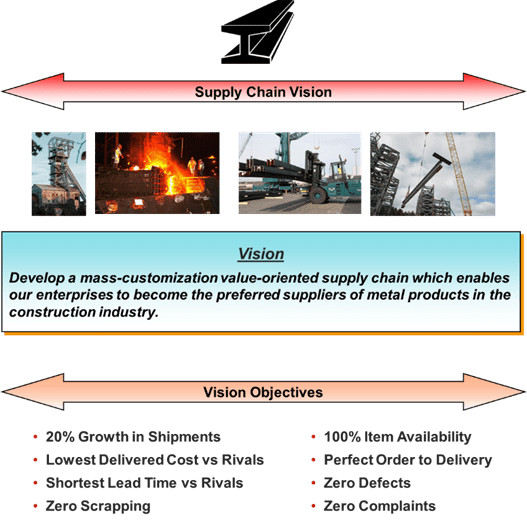

We know what we want, i.e., we have a vision.

We know where we’re at versus what we want, i.e., we did our reality check.

We see the disparities between our present-state & future-state performances, i.e., we mind the gaps in our supply chain operations.

The next step in building our supply chains is to make a roadmap, a series of steps which taken together would lead us to a desired future state of supply chain performance. These steps would bridge or bypass the gaps we identified by comparing our present operations to what we envisioned.

It sounds like Project management methodology, in which we define and plan tasks, resources, accountabilities, and schedules for a complex undertaking. Typically, in project management, we identify which tasks goes first and determine milestones, the points on a project’s path in which we meet the criteria for a task’s achievements. We also determine whether our accomplishments are aligned with our objectives.

But the roadmap of building supply chains is not composed of tasks, but solutions, in which we address problems the gaps we had identified represent. Project management is more about making a solution into reality, as the project which we are undertaking is by itself the solution (or set of solutions) to a problem. In managing a project, we know what we need to do; we clarify the tasks, plan the support, assign the people who’d be responsible, and determine the schedule and costs. In the building of supply chains, however, we define and solve problems from the gaps we observed in our operations. We make visible the challenges from the realities of individual operations, we look for the root-causes, and we clarify the problems of each; we then set out to solve them.

Managing a project is like planning a road trip through known territory. We are familiar with the terrain and the traffic. We make out a route via streets & highways to reach our destination. And we estimate how long and how much it will cost it will take to get there. Our roadmap is a route passing through existing territories and networks.

Drawing a supply-chain-building roadmap, however, is not only like planning a road trip but also constructing the road itself. The territory between the starting point and destination requires development. It’s like building a highway through a jungle. We would need to survey the terrain, obtain resources, determine the best pathways, and invest in the infrastructure. We would need to build the road for the roadmap.

Unlike project management, drawing the supply chain roadmap identifies problems from performance gaps in supply chain operations. The problems and their respective solutions are what would be the components of the roadmap from the present state to the envisioned future state. We just need to plan which ones we solve first.

Given that the supply-chain-building roadmap is focused toward solving problems, we’d not precisely know how long and how much we would need to complete it. The purpose of the roadmap would be to lay out the problems we can expect to encounter and must solve,

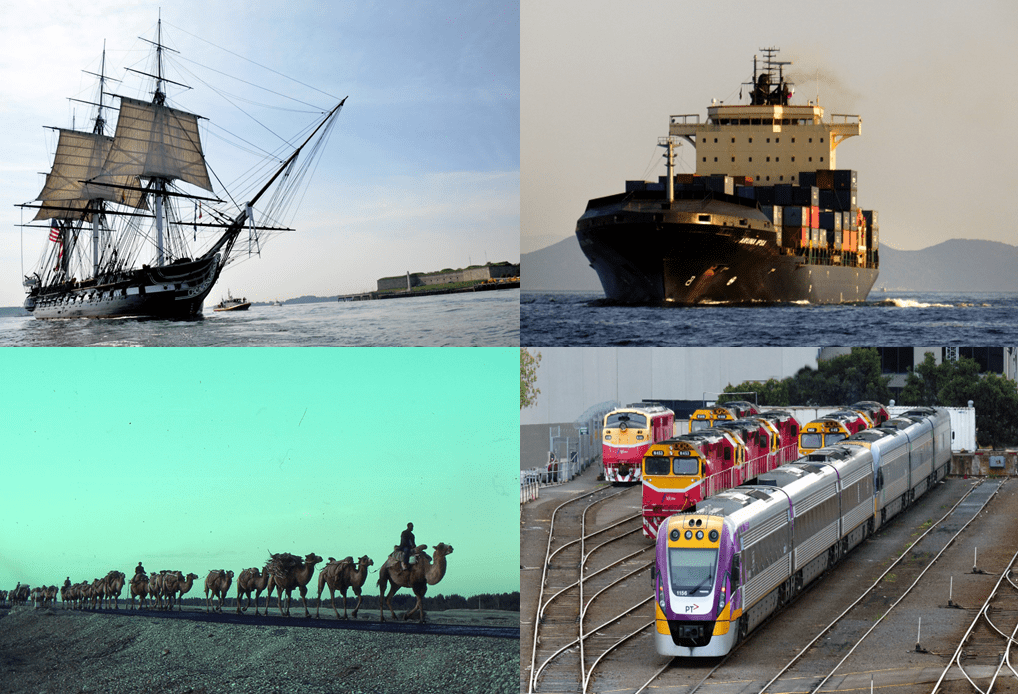

It may be argued that there are already structures & systems in place. There are already established manufacturing & logistics networks and multitudes of vendor with long track records. There are functioning global supply chains in place. Why would we need to build new systems & structures?

Despite the existence & growth of local & global infrastructure (e.g. ports, ships, trade routes, manufacturing & logistics facilities) many supply chains have stagnated performance-wise. An extreme observation would be that supply chains have become trapped in their own infrastructure.

Supply chain management has generally been about working with available resources, systems, & structures. Managers improve operations based on what exists, such as ports, trade routes, facilities. Enterprises have put a lot of focus, for example, on transportation turn-around times, outright inventory reductions, and head count cutbacks to uplift their operations’ productivities.

But working with what we have can go only so far in improving our supply chains. Many supply chains have plateaued in performance such as inventory turnovers and delivery performances staying flat over time. It doesn’t help that disruptions such as weather & climate disturbances (e.g. drought limiting port traffic at the Panama Canal), security diversions (e.g., ships avoiding Red Sea missile attacks), and more complicated regulations (e.g., requirements to disclose supply chain sources) have made it more difficult to optimise supply chains.

Managing supply chains per se is therefore not enough. We need to build better structures & systems from the ones we have at present. The supply-chain-building roadmap we would draw would be about solving the problems in setting up new structures & system based on the gaps we had observed between our present-state operational performances and desired future-state results.

We know our vision, we accept our reality, and we see the gaps that we need to close. We identify problems in building our supply chains, and plan which ones we will solve in sequence or simultaneously, bearing in mind that the problem-solving path we choose to take would be consistent with our vision.