On October 6, 1973, Egyptian and Syrian military forces launched attacks on Israel. It was Yom Kippur, Israel’s holiest religious holiday and despite defensive contingencies, the Jewish state’s citizens were taken by surprise as thousands of tanks, artillery pieces, and soldiers invaded the Golan Heights at the north and at the Sinai Peninsula at the south.

While media attention focused on the Egyptian invasion at the Sinai, Israel’s survival hung on a balance from the Syrian offensive at the Golan Heights. The Syrians had brought 1,200 Soviet-made tanks backed by 1,000 artillery pieces and another 1,000 armoured personnel carriers (APCs). Israel had only up to 250 tanks going into battle. Syria’s Soviet-made surface-to-air (SAM) missile batteries shot down responding Israeli Air Force (IAF) jet fighters, effectively neutralising air support. It was a duel to be determined by two ground armies in which the odds were stacked in favour for the Syrians. It was a life-or-death struggle for Israel. [1]

Within 100 hours from start of the attack, however, Israel had beaten back the Syrians. Israeli professionalism, gallantry, coupled with advantages in terrain, had prevailed. Some would say it was a miracle.

The Syrians had hit all engaging Israeli tanks during the battle of the Golan Heights. Of the 250 Israeli tanks that Syria had knocked out, 150 of those tanks returned to battle after they were repaired within 24 hours. Some of the 150 Israeli tanks were even hit more than once but still returned to battle within hours.

At the height of the fighting, Israeli tank crews brought their damaged vehicles to repair centres behind front-lines. Soldiers would rescue tank crews and towed the tanks back. Logistics personnel made sure there were ample stocks of spare parts as mechanics and engineers quickly fixed the tanks and made them ready for service within hours. Tank crews meanwhile used the respite to rest and eat. [2]

The Syrians had no such system. Tank crews would simply abandon their damaged tanks. There was no replacement or repair for any Syrian tank that was hit. The Israeli tanks, meanwhile, returned to the field again and again to engage their enemies. Even at overwhelming odds of up to 10 Syrian tanks for each one from Israel, the Syrians could not keep up. After four (4) days of fighting, the Syrians withdrew. Israel emerged victorious.

The Yom Kippur war was a testament how the Israeli military valued its soldiers and equipment. While its Arab opponents relied on the Soviet military doctrine of unleashing large numbers of tanks and soldiers, Israel opted on the ability to rotate its weaponry on the battlefield. The Israel military’s system of maintaining their equipment and rotating them back to service undoubtedly contributed to its victory in the battle for the Golan Heights.

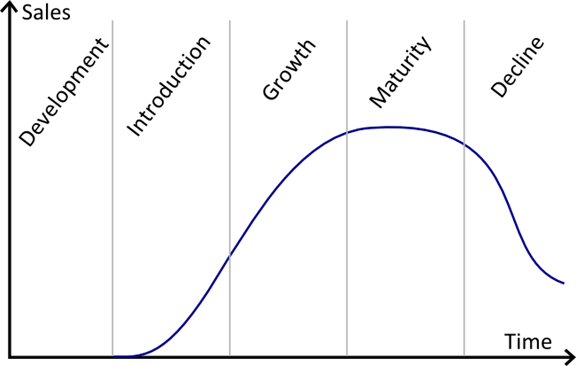

Maintenance of fixed assets is a commonly neglected area in enterprises. Buildings, trucks, material handling equipment, production machinery, and office hardware are part and parcel of most, if not all, enteprise operations. Yet, some enterprise executives don’t see the value of maintenance of such assets in good running working condition.

We hear the complaints all the time:

- A purchasing assistant has to share her laptop with a colleague whose desktop personal computer is waiting to be fixed;

- A quality control laboratory technician delays the release of a finished product because a replacement part for her broken-down testing machine hasn’t arrived yet;

- Employees on a shipping dock can’t finish loading trucks because their forklifts constantly stall;

- A building roof leaks when it rains and disrupts production on an assembly line.

Enterprise executives should not view maintenance as a burden. They should see it as an opportunity for competitive advantage.

Setting up a maintenance program does not require management re-invention. As with any management process, it involves setting goals, formulating strategies, and establishing policies.

Supply chain engineers (SCE’s) can help enterprises assess the system of managing the procurement and inventories of spare parts and marry it with the performance measurement of operations.

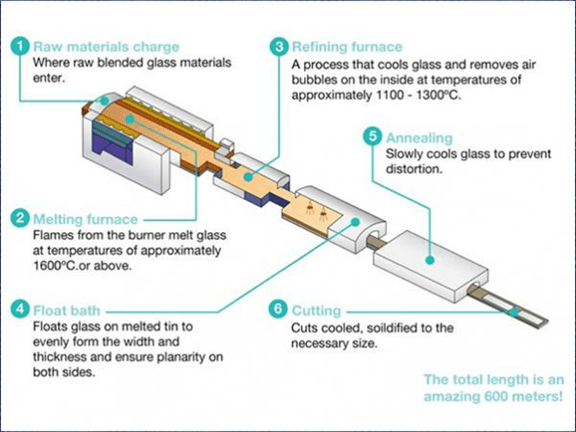

Maintenance may be daunting especially for supply chains that employ complicated processes and equipment. All the more reason for enterprises to engage the engineering prowess of SCE’s who can assess and untangle the myriad complexities of equipment set-ups and recommend solutions to optimise the balance between operational uptimes and maintenance downtimes.

The Israeli military in 1973 made sure their soldiers had the support of a superior maintenance system to defend their country. The repair centres behind the front-lines those fateful days at the Golan Heights had enough tools, well-trained crews, and a well-stocked inventory of parts to fix damaged tanks and equipment and bring them back to battle.

Maintenance made a difference to a country’s miraculous victory. What more can it do for enterprises in highly competitive arenas.

[1] Jerry Asher with Eric Hammel, Duel for the Golan, (New York, New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc., 1987) book jacket.

[2] Ibid, page 192.