The phrase, “elephant in the room,” is said to have originated from a fable by Ivan Krylov that tells about “a man who goes to a museum and notices all sorts of tiny things, but fails to notice an elephant.” It has become a favourite expression for an obvious problem or issue that for some reason gets muddled, forgotten, or avoided.

Just about every supply chain has an elephant in its room and in many cases, it’s called non-moving inventory.

Non-moving inventories are items that have ended up idle in storage or on the factory floor for extended periods of time. Non-moving inventories can be raw materials, packaging materials, spare parts, work-in-process, or finished goods. They are merchandise that were acquired or produced at a cost but have become unattractive in value.

Non-moving inventories end up as they are for a variety of reasons:

- the enterprise produced more than what could actually be sold;

- items are defective, rejections, damaged, or were returned from customers;

- items are old, obsolete, expired, or discontinued;

Whatever the reason, enterprise executives would see them as one thing: a nuisance that takes up valuable space and ties up working capital.

But they are more than a nuisance. Non-moving inventories are cash investments that went to naught, as they had lost their selling value. They are blots to marketers who see them not only as visible failures of their promotional strategies but also as barriers to introducing new products. Some enterprises hold their marketing and sales executives accountable for non-moving inventories and would insist they lead in running them out before any new product is introduced.

Non-moving inventories are potential threats. When non-moving inventories grow in size or quantity, they not only become the elephants in the stock-room or storage facility, they also become risks. An extreme example is when non-moving ammonium nitrate fertiliser exploded in a Beirut, Lebanon warehouse in 2020: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/04/huge-explosion-beirut-lebanon-shatters-windows-rocks-buildings

The good news is many non-moving inventories don’t end up exploding. The bad news is that even if they don’t explode, they are a potential threat to the enterprise’s balance sheet and to its future growth.

Despite their nuisance and threat, many enterprises take for granted non-moving inventories and instead try to get them away from their sight.

A case in point: a large corporation that makes steel beams and heavy metal parts hired a chief information officer (CIO) to streamline the inventory system. To appreciate the company’s products and materials, the new CIO toured the corporation’s main factory and warehouse which was just outside the city. He noticed a huge pile of rusting steel products at a far side of the facility and asked what they were. The plant manager who was his tour guide said the items were scrap.

The CIO asked how come there’s so much of the “scrap?”

The plant manager said, “I don’t know. They’ve been sitting there for years ever since I was hired.”

When the CIO reported the “scrap” to the Chief Executive Officer, the latter was outraged.

“They [his chief finance officer & chief manufacturing officer] told me that they got rid of that stuff many years ago!”, the CEO exclaimed.

The CEO summoned the CFO and Chief Manufacturing Officer (CMfgO) and ordered a thorough audit.

The CFO and CMfgO were furious at the new CIO for making them look bad for exposing the hidden inventories. Within a few weeks, they drove the CIO to resign after they constantly hurled negative comments about him and refused to cooperate with him in improving the inventory system.

As for the non-moving inventories, they continued to sit in that far corner of the company’s factory, where executives once again forgot about them.

For the steel company, the non-moving inventories would come back to haunt the executives. This is especially true as the non-moving items would multiply in size and take up more space. It would become a problem when the enterprise entered hard times and had difficulty paying debts. Auditors would no doubt point to the non-moving inventories as where the company’s cash is tied up.

How then does one get rid of non-moving inventories? The answers are straightforward but can be controversial:

Sell non-moving inventories at the best but most attractive price possible. If one can only sell them at scrap value, so be it.

Some finance executives, however, caution against such drastic selling. It’s one thing to convert non-moving inventories to cash; it’s another to sell them very cheaply. Losses in balance sheets attract negative attention especially if an enterprise is publicly listed. But if one wants to once and for all remove the elephant in the room, this is usually the number one solution, whatever the hit it will bring to an enterprise’s financial reputation.

This is worse than selling at scrap value but sometimes it’s the next best option if the enterprise needs valuable space and the alternative is to pay dearly for more space.

Throwing stuff away can also be a hassle given all the compliance protocols it might entail (e.g. environmental impact). But if the items are toxic or dangerous to carry for extended periods of time, the enterprise might not have much of a choice.

- Salvage Whatever Can Be Recycled or Reused

Some enterprises would invest in salvaging what can be reusable or re-saleable from non-moving inventories. It’s never an attractive option as it will often require significant expense in time, materials, and equipment. But it can be a compromise in that salvaging non-moving stock may not result in a sudden hit to an enterprise’s accounting books. It would also be an opportunity for enterprises to dispose items gradually while getting something back in return.

- Process the Work-In-Process (WIP)

Many manufacturing enterprises have work-in-process inventories (WIP). They’re the stuff that lie between production operations, usually waiting their turn for the next step in a manufacturing process.

Some manufacturers, however, keep their WIP waiting too long, sometimes too long that the WIP loses value from deterioration and expiration. This happens when manufacturers don’t follow first-in first-out (FIFO), customers cancel orders while items are in production, or managers allow other orders to “jump the line” or move other WIP ahead of others.

I’ve seen WIP stored in one place for more than three (3) years, hidden away in a dark corner of a factory, their values long written off by auditors who thought they were losses.

Even if written off, WIP takes up space and represent poor management resulting in waste. And even as operations managers may succeed in hiding and getting rid of them, poor manufacturing practices will undoubtedly result in more WIP time to time.

The answer to avoiding non-moving WIP is to process them right away. If they are no longer needed, then either the manufacturing manager should process them anyway, scrap them, or salvage some value from them. Manufacturing managers should also have a policy to always process all the WIP within a maximum number of days, if not hours.

The best way to get rid of non-moving inventories is to avoid having them in the first place. Unfortunately, many enterprises are stuck with them, in one form or another. Eventually, non-moving inventories become easy to spot as an elephant in a room would be. They’d be that pile of junk, that stack of unidentified boxes, that pallet of dusty cartons, those drums behind the building, or that huge tank that managers have no idea what it contains.

Any non-moving inventory will stick out like a sore thumb. We may try to ignore them but they’ll grow into something larger and harder to afford if we let them.

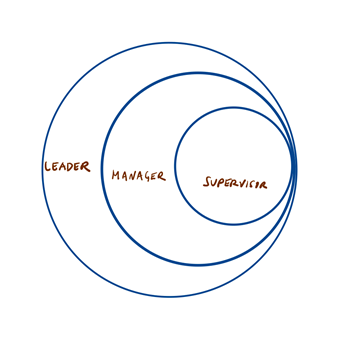

Let’s not let them. Enterprises should get rid of them as fast as possible. Teamwork with financial auditors and accountants would help because when one has to remove an elephant, one needs all the help one can get.

About Overtimers Anonymous