Do we really need a new highway?

Metropolitan Manila, Philippines, has one of the worst urban traffic congestions on Earth (at least before the pandemic of 2020 forced people to stop travelling). This has led to a number of corporations and wealthy individuals to propose new roads, bridges, and tunnels.

The proposals cite the obvious problem of traffic gridlock and the resulting negative effect on productivity. The city’s leading agency, the Metro-Manila Development Authority (MMDA) believes the country’s economy loses an estimated PhP 3.5 billion ($USD 70 million) daily due to traffic congestion.

For so many years, the Philippine government has extended expressways north and south of Manila, built or refurbished new bridges, and even initiated river ferries to reduce travel times within the city. At the end of 2019, however, people were still complaining about being stuck in traffic for hours. This has led the government, investors, and private corporations to propose and initiate new projects. These include elevated expressways, more bridges, and a subterranean commuter train that will traverse underneath the city.

Government and some so-called experts believe these new projects when completed will ease traffic and alleviate the woes of commuters and automobile drivers.

But will it, really?

Los Angeles County, California, USA, has lots of highways. Over many years, the city has seen more freeways built, expanded, and improved. It takes only minutes to travel from one place to another, even if the distance is 30 to 40 miles (48 to 64 kilometres) across the county. LA’s freeways is just a subset of the United States’ Interstate expressway system which allows people to drive across the country seamlessly.

In recent years, however, traffic along the Los Angeles freeways have gotten worse. Gridlocks are common not only during morning and evening rush hours but also even during weekends. And even as the state of California adds more to its freeways, the traffic has grown longer year after year.

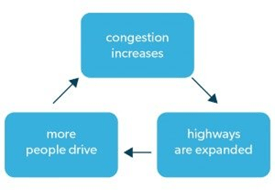

Expanding road capacity doesn’t necessarily reduce traffic; it actually may increase it. It’s called Induced Travel Demand (ITD). As more roads are built, more drivers together with their automobiles emerge and eat up the added capacity.

ITD has been proven in urban centres not only at Los Angeles but in cities around the world such as Beijing and London. It puts truth to the adage: “if you build it, they will come.”

The phenomenon of ITD, however, doesn’t apply to all places. The Louisville-Southern Indiana Ohio River Bridges Project in the USA, for example, saw travel demand reducing instead of increasing despite forecasts to the contrary.

In brief, increasing capacity can cause a corresponding increase in demand. In contrast, increasing capacity can result in decreasing demand. In both scenarios, engineers don’t get what they expected in terms of beneficial results.

Adding capacity always seemed to be an obvious solution to increasing demand. In reality, however, it’s not.

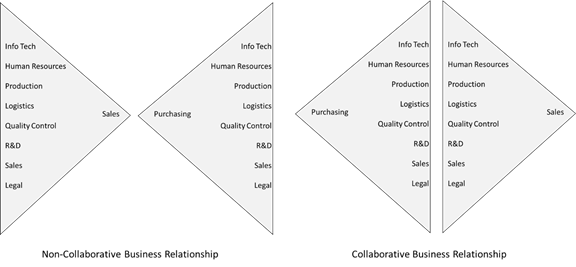

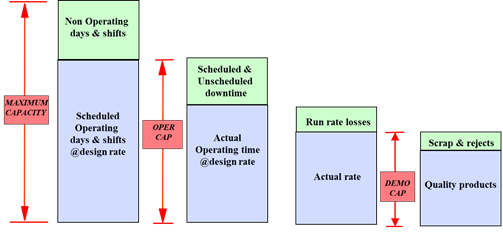

Enterprises often invest in additional capacity when supply chains fall short in deliveries due to reasons such as production not being able to keep up with orders or because there were not enough trucks to load items.

It’s obvious, the executives would say. Manufacturing is running flat-out and we need more trucks.

It goes further. Logistics managers would say they need more storage space and more forklifts, on top of more trucks. Purchasing managers ask to hire more staff to find more vendors. Manufacturing would want their facilities expanded to accommodate more equipment.

Justification is supposedly straightforward. Engineers extrapolate present-day numbers with trends into the future. Space will run out. Production capacity will continue to run behind. There will be more truckloads.

The extrapolations that engineers use to justify added capacities aren’t even based on simplified mathematics but on elaborate algorithms certified by experts and established as valid for years.

So, why then do projects fail to reap benefits? Why does demand suddenly increase and traffic get worse? Or why does demand fall off after new capacity is installed?

Because the forecasts, simply put and for what they were worth, are wrong. Or to put it more concisely: the forecasting is wrong.

Urban planners often don’t take into account Induced Travel Demand because their forecasting only considers historic trends in demand. They fail to see that sociological factors come into play when new roads and bridges are built. Simply put, when people see a new road, they want to drive on it. And the more a city boasts about the added capacity of a new road, the more the people are encouraged to change their habits of commute to use it. More people drive and more cars are bought. Congestion on the new road increases.

In the Louisville-Southern Indiana Ohio River Bridges Project, the forecasting model engineers used assumed traffic would increase because there would be more commuters and motorists. The forecasting model was based on surveys and mathematical algorithms.

What the forecasting model didn’t take into account was that people’s behaviours change. They don’t remain necessarily constant. Hence, as the Louisville economy and demographics evolved, the patterns of commuters and motorists also changed. Demand actually fell. The forecast was wrong.

Engineers in the United States now realise that justifying new capacities whether it be for new highway infrastructure or for new machinery for manufacturing should not be based on forecasting alone.

It should be based on what the problem is.

Capacity is not the problem when it comes to traffic.

Capacity is not the problem when supply is not meeting customer demand.

For urban planners, it should start from questions like:

- Where do we want people to reside and work?

- How much public transportation do we want?

- How many high-rise buildings should we allow to be built and where?

- Where do we locate our airports and seaports?

- Do we really need a new highways and airports?

For supply chains, questions arising about capacity shortfalls should focus toward:

- Do we need more or less customers to deliver to?

- Who do we want to sell and deliver to in the future?

- Who are the customers that are buying more or less of our products?

- Do we need to sell more new products or do we need to sell fewer?

- Are our manufacturing facilities too big and too far from customers?

- Should we centralise or put up satellite depots and service centres?

- Are we satisfied with our transportation set-up?

Forecasts are the bases of justification for new capacity projects. Unfortunately, forecasts cannot be depended on to be precisely accurate. In the first place, forecasting by itself, despite the modern-day algorithms, can never be counted on to provide a clear picture of the future.

The error in justifying new capacity is in using the shortfall of capacity alone as a reason. Engineers have realised that they should look at the causes behind the capacity shortfall and not by its symptoms.

We won’t ease traffic if we just build more roads.

We won’t benefit by just adding more machines or trucks.

We need to address the causes that underlie the effects.

We build not only to accommodate. We build to solve.