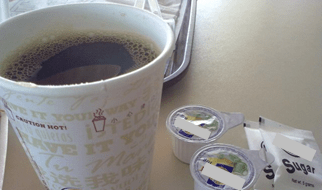

The fast-food restaurant drive-thru I go to every Sunday morning hasn’t been serving the liquid creamers that accompany the coffee I order with my meals.

At first, they said the creamers were out of stock. A week later, they said they can only serve one (1) creamer instead of the two (2) that should come with every coffee order. Finally, they substituted the coffee creamer with a non-dairy powder cream in a sachet.

The fast-food company saved money in all three (3) instances. They saved when they served coffee without any creamer or with just one instead of the usual two. They also saved when they started serving the powdered creamer in sachets as the liquid creamer is more expensive.

The fast-food company can claim savings but did it deliver value?

In his seminal book, Competitive Advantage,[1] Michael Porter introduced the value chain, a representation of a firm’s “collection of activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support [the firm’s] product.”

Value is the “amount buyers are willing to pay for what a firm provides them.” The typical strategy of the firm is to create value that “exceeds the cost of doing so.” According to Porter, value is the key to competitive positioning.

The fast-food company normally served two (2) 10-ml cups of imported liquid creamer with every coffee order. It was something I look forwarded to and expected whenever I went to the fast-food company’s drive-thru. When the fast-food drive-thru stopped serving the creamer, I was not happy. I felt I was no longer getting my money’s worth from my coffee order.

Bundling two (2) 10-ml creamers and two (2) packets of sugar was standard for every coffee order, according to the drive-thru attendant. Unfortunately, the fast-food drive-thru no longer had the stock and substituted the creamer with a cheaper sachet of locally produced non-dairy powder.

The fast-food company apparently thought substituting the imported creamer with a cheaper local product would be no big deal. The management of the fast-food company probably didn’t believe its customers would buy less of its coffee, even with the downgrade.

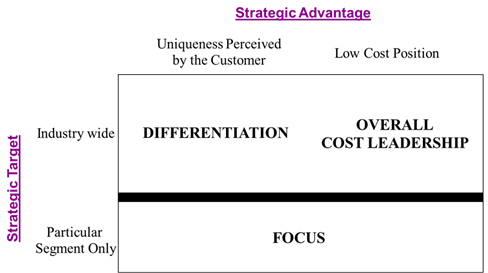

The cost of all the activities in the value chain must be less than the price of the product. The difference between the price and the cost is the margin. Enterprise executives tend to cut costs or differentiate their products to maximise margins.

The problem arises when customers like me perceive a lower worth of the product as a result of the enterprise’s cost-cutting. Perceived lower worth leads customers turning away from the enterprise and opting for alternatives from the competition, resulting in lower demand for the enterprise’s product.

Many enterprises see-saw between cutting costs and differentiating their products as they struggle to maintain their products’ profit margins. When they see costs going up, some enterprises buy cheaper materials and services. When they see demand slowing, they spend more for product development and advertisement of their product’s features. In either case, the enterprise ends up losing customers or spending more than it should.

All functions in an enterprise make up its value chain. Whether it be purchasing, marketing, logistics, sales, manufacturing, finance, accounting, human resources, information technology (IT) services, legal, public relations, research & development, etcetera–every department and individual play a part in delivering value for the enterprise. Every one in an enterprise contributes. There is no exemption. If the value chain is to be competitive, everyone has to work and to work together toward the common cause of maximising the margins of the enterprise’s products.

Every part of the value chain must be productive. Productivity drives value.

Productivity is output over input. In the value chain, productivity is the output as delivered and accepted by customers versus how much was inputted in doing so.

That means whatever function we work in, we must deliver output that would benefit the enterprise’s product margins. Our performance, no matter how seemingly small or irrelevant, contributes to the value chain.

Some of us equate value chains with supply chains. This is wrong thinking and it is detrimental to an enterprise’s productivity. Whereas the supply chain’s basic functions like purchasing, manufacturing, and logistics directly add value to a product, roles such as legal, human resources, marketing, sales, engineering, information technology, and research & development (R&D) are just as equally important.

Human resources professionals hire talented people to staff the enterprise’s organisation. In-house legal counsels ensure products are compliant to local laws and regulations and defend the enterprise’s products’ intellectual properties. Finance executives ensure the capital needs for products. Marketing cultivates ideas for R&D to develop into reality.

A condiment such as a coffee creamer may seem trivial. For value chains, nothing is trivial. Every detail and process have a bearing on how a product’s value chain will bring worth to customers.

The fast-food company may dismiss my disappointment if it turns out I’m alone in complaining about a downgraded coffee creamer. If a vast majority of its customers continue to consume the fast-food company’s coffee, then well and good, the enterprise would have saved money without any dent to its coffee’s perceived value.

But if my sentiments are shared with many coffee drinkers who decide to turn away and find alternatives, then the enterprise would no doubt be strongly encouraged to improve the productivity of its value chain. Perhaps it will study how better to source its imported creamer to ensure it will always be bundled with the coffee it sells.

In the meantime, I decided to get my Sunday morning coffee from the fast-food company’s competitor.

[1] Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage, (New York, N.Y. : The Free Press, 1985), pp. 36-38