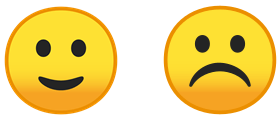

Most executives like performance measures. Otherwise known as metrics, key performance indicators (KPI’s), analytics, or scorecards, enterprises embrace performance measures as a means to assess how their businesses are doing.

The point of a performance measure is to check how an individual or team is doing against a target that is set by superiors. (No matter what people may say, it’s always the superior who sets the targets). Targets are set in line with strategic goals. Individuals and teams strive to perform such that resulting measures would meet targets to attain the goals.

But after more than twenty (20) long years since they’ve become popular, performance measures are no longer good enough, especially for supply chains.

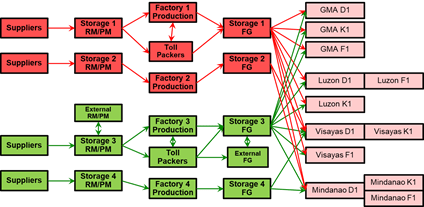

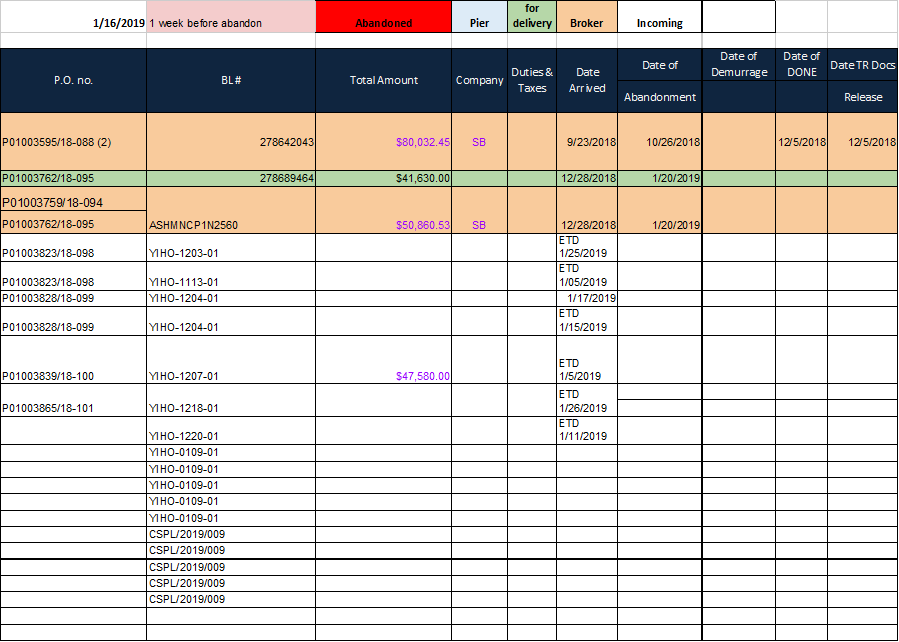

Supply chains are product and service streams. Materials, merchandise, and information (printed and digital) flow through networks within and between enterprises. From one operational step to the next, products and services transcend in value as they make their way to their final destinations: the end users.

Supply chains are sensitive to disruption. When a disruption hits one process, every part of the supply chain feels it. A delay in the loading of a truck, for instance, may entail a change in production schedules at a manufacturing facility it is supposed to deliver to, which in turn may cause a shortage of a product the facility is supposed to make.

Performance measures are popular as many people could relate to them. They are simple and easy to appreciate. They show how a person’s work is doing versus a target that fits to that person’s tasks. The performance target would be linked to higher levels of performance measures that would finally connect to a strategic goal.

Unfortunately, performance measures do not work very well when there are disruptions. Whereas they are designed such that different levels of an organisation can be made accountable for them, performance measures are not flexible to changing circumstances.

For example, a production line supervisor is accountable for how many overtime hours his crew works in a week. His target is that each crew member does not work more than 4 out of 40 hours of overtime per week. He controls the overtime by rotating his crew members’ leaves such that not many of them have days off at the same time. But if the supervisor receives a surprise rush order such that he has to make double his weekly volume, he would be forced to ask his crew to go on overtime to meet that order. His boss, however, would ask him later to explain why he exceeded his weekly overtime target.

Disruptions are nothing new for supply chains. They can be big or small. They are the results of both adversities and opportunities And they can come periodically or frequently. They are never identical in cause and they sometimes come in the most mundane manner, like a surprise doubling of a production order such as in the example mentioned above

Performance measures work when supply chains run routinely, much like in a game of sports. Sports games operate under fixed sets of rules and conditions. Players score and meet goals to win. But if it rains, the game stops. In similar fashion, supply chain professionals perform to achieve objectives set by schedules under favourable and predictable working conditions. But if someone changes the schedule or everyone has to go home because of a disruption like a virus-causing government-mandated lock-down, the performance measures become useless.

Disruptions are normal. They aren’t exceptions. Disruptions occur often as a result of frequent adversities and opportunities that ripple through the fast-paced interconnected world we live in.

What supply chains need are monitoring systems that tell us not only what is going on but also notify us when there is a need to respond. We need monitoring systems that will tell us about upcoming disruptions and give us time to take action.

Two things comprise a monitoring system: visibility and guidance. Visibility in the form of real-time information and guidance in the form of alerts to events that merit a response.

An example is a fuel gauge in a car. The gauge provides visibility on how much fuel is there in a tank. It also gives guidance via a flashing light that alerts the driver that the fuel tank is almost empty.

Monitoring systems are not new to supply chains. Manufacturing managers harness instruments and gauges to monitor production lines and facilitate process control. A number of enterprises have adopted technologies such as radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags, block-chains, and artificially intelligent command-and-control systems to oversee supply chains even from long distances.

Many enterprises, however, have had little success in mitigating disruption in their supply chains despite the growth of high-tech monitoring systems. This is because many monitoring systems aren’t focused towards disruption. Instead, they are geared towards performance for the sake of measuring results versus strategic goals, which as aforementioned don’t really contribute very much in a frequently disruptive environment.

We, therefore, need to re-orient supply chains towards monitoring for disruption, not performance. By watching out for disruption and responding to it, supply chains would be able to muster resources to mitigate it, even perhaps take advantage of it.

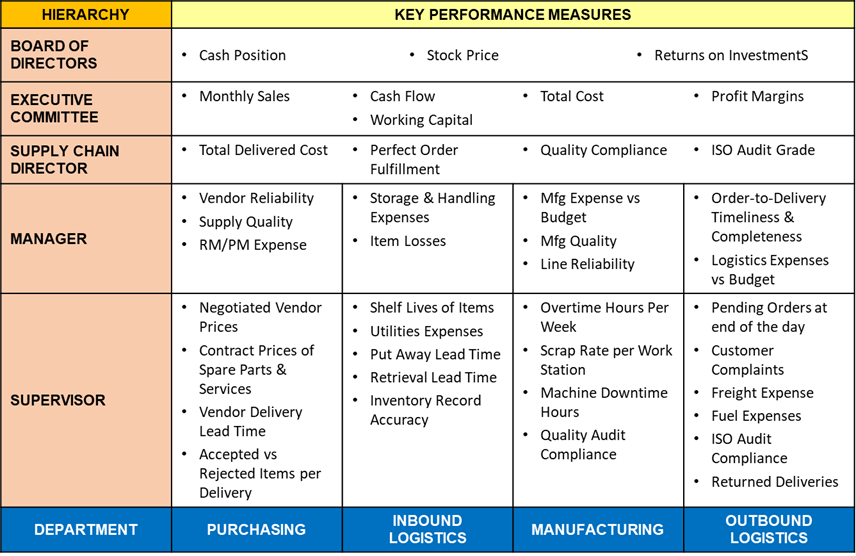

One doesn’t have to start with an intricate, complicated or expensive system. One can begin with simple reports from various operations along the chain. For instance, vendors, brokerages firms, and shipping companies can email the status of orders for imported materials.

A status report such as the one above can tell stakeholders about impending issues such as a shipment that’s about to be considered abandoned and subject to penalties.

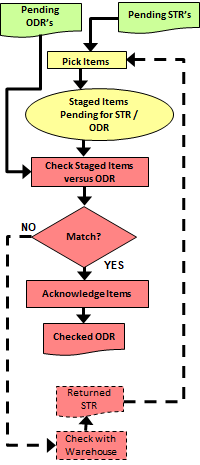

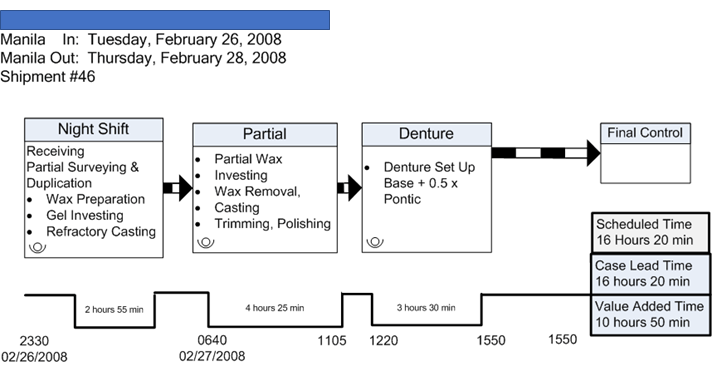

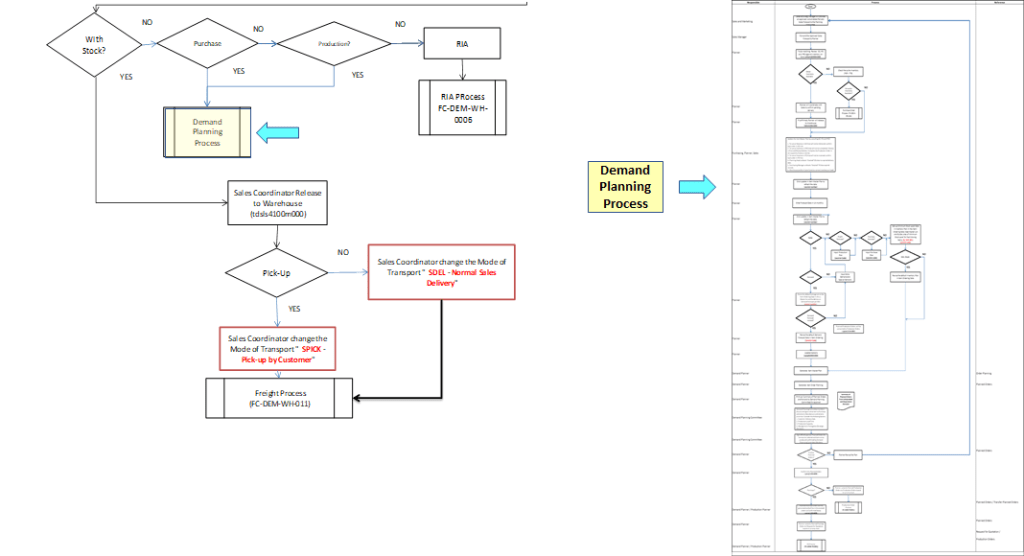

Supply chain engineers can make improvements step-by-step by tailoring feedback systems to fit different processes. SMS texts summarising daily customer orders, entered orders in the database, communicated factory orders, MRP II real-time plans are examples.

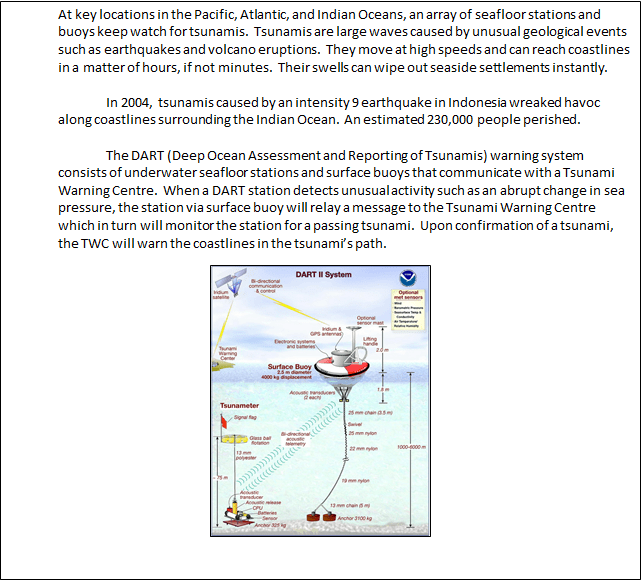

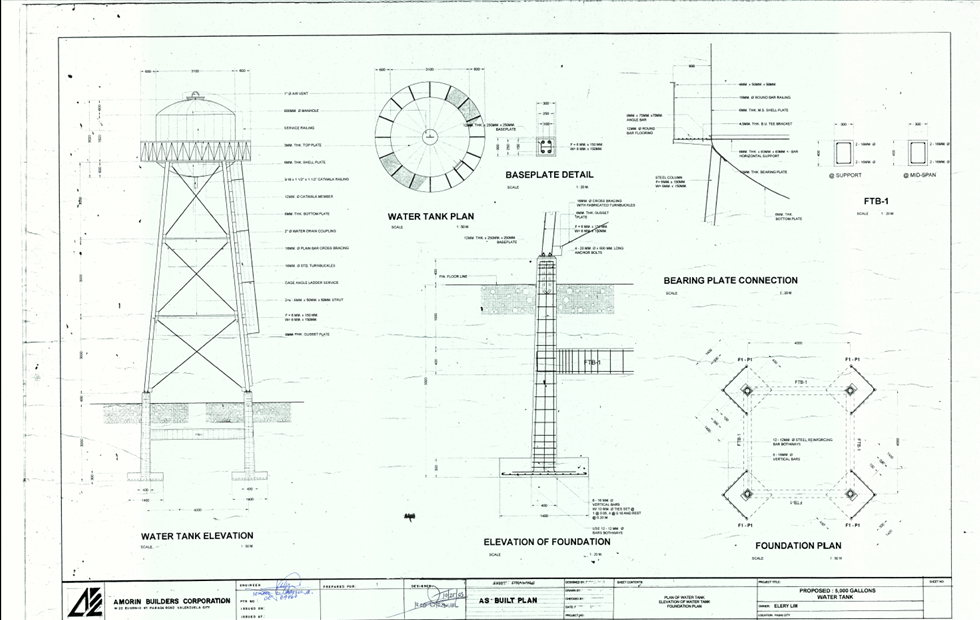

A supply chain monitoring system can also be like a tsunami warning system:

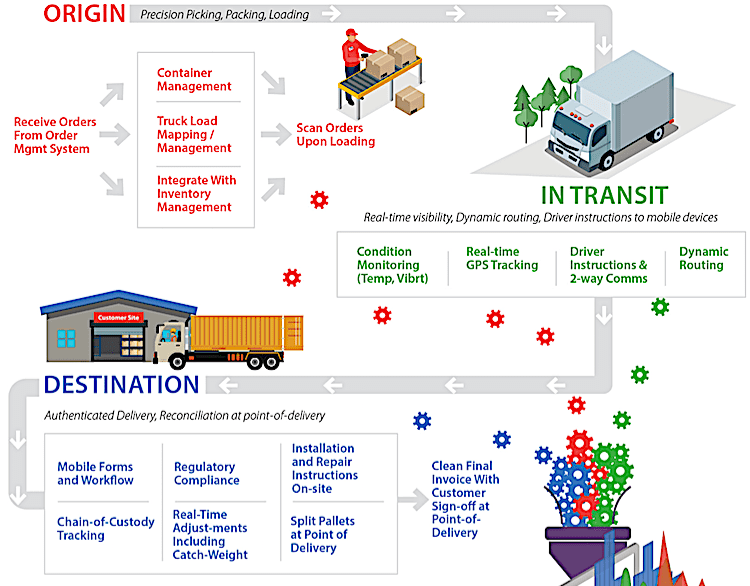

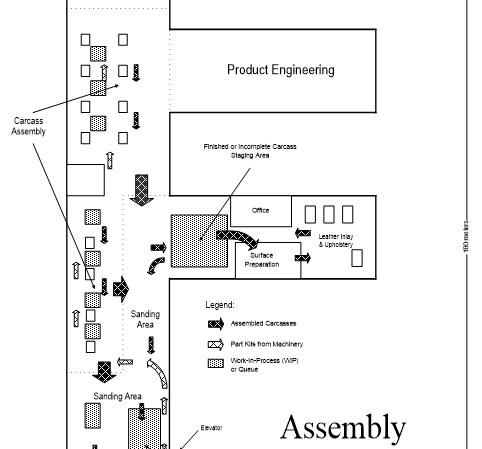

Or it can be manifested like a dashboard for supply chain professionals to see:

Whatever the design, the purpose of the monitoring system is to allow stakeholders to watch out for disruption and respond when needed.

Performance measures have not proven to be helpful in our disruptive-driven world. We need monitoring systems that provide visibility and guidance especially for supply chains. They don’t have to be complicated; they just have to be adequate enough to bring attention to disruptions.

Disruptions are a result of both adversity and opportunity. In either case, it’s always best to be one step ahead whether it be to mitigate or to take advantage of whatever’s out there.