Dear Industrial Engineer:

I come to you as a fellow Industrial Engineer (IE) with a message.

It’s time for us to rise up.

For years, or should I say decades, Industrial Engineering (IE) has been an un-recognized engineering discipline.

Many engineers—e.g. civil, mechanical, chemical, electrical—look at us as fakes.

Industrial Engineers (IEs) aren’t recognized as technically proficient builders or problem solvers at par with other engineering disciplines. Even if many of us have professional licenses issued from places like the United States and Europe, we are not respected in many parts of the world.

Most enterprises and organisations see us as more of management professionals than engineers. They perceive the specialized courses we take, such as time & motion studies, operations research (OR), facilities planning and inventory systems modelling, as management subjects than technical specializations. This is despite the fact that we are educated in advanced mathematics and sciences such as calculus, chemistry, and physics, and in engineering courses such as statics & dynamics, materials science, and electrical systems.

We are competent in reading and drafting engineering drawings and many of us know how to operate equipment like lathes, drills, presses, and milling machines. We specialize in advanced statistical models such as linear/non-linear programming, queuing theory, and transportation algorithms.

Despite our engineering prowess, very few understand what IEs do. We ourselves don’t have a clear picture of what Industrial Engineering is. We’re always finding ourselves struggling to explain what IE is to our peers, co-workers, friends, and fellow family members.

The problem is with the title itself. What does the “Industrial” in Industrial Engineer mean anyway?

People know what a civil, chemical, mechanical, or electrical engineer is just by the titles. But with Industrial Engineer, we have to explain it and most, if not we, still wouldn’t get it.

True, many of us IEs, thanks to our training and experience, have successful careers. Many of us have become top-notch executives and well-off entrepreneurs.

It would be nice, however, if we could just have a little more recognition and apply what we know as IEs. And this is exactly what this letter is all about.

We are in the midst of the worst crisis to hit the globe since World War II. The COVID-19 disease has ravaged communities and brought economies to a standstill. Enterprises and individuals have lost earnings and incomes as people get sick or are forced to stay home. Many products are in short supply as manufacturing and logistics facilities have become undermanned or short of materials. Border closings have delayed or stopped deliveries altogether.

COVID-19 is the latest and the worst in a series of adversities that has befallen supply chains. It isn’t the first and it will not be the last.

Year after year, adversities ranging from natural disasters, cyber-data malware, and trade tariffs have made life difficult for supply chains. From the September 11, 2001 terror attacks to the climate change crisis, adversities have been buffeting businesses and societies. They come small but frequently (as in daily traffic jams) or big and infrequently (such as typhoons). They can come in the form of interruptions (e.g. power failure) or as a man-made business trend (e.g. a new mobile app that makes obsolete traditional package deliveries).

As supply chains have become global and more sophisticated, they have become more and more sensitive to adversities. The challenge to supply chain productivity, and to enterprise survival, is very real.

We as IEs are in the best position to deal with adversities. We have the expertise, the talent, and the tools.

For example, amid the crisis of COVID-19, we as IEs can help hospitals reduce wait times for patients via our knowledge of Operations Research (OR). We can set up forecasting and inventory models to assist hospitals to avoid out-of-stock incidences for medical equipment and supplies. We can help in improving schedules and reducing wastage in medicines and supplies.

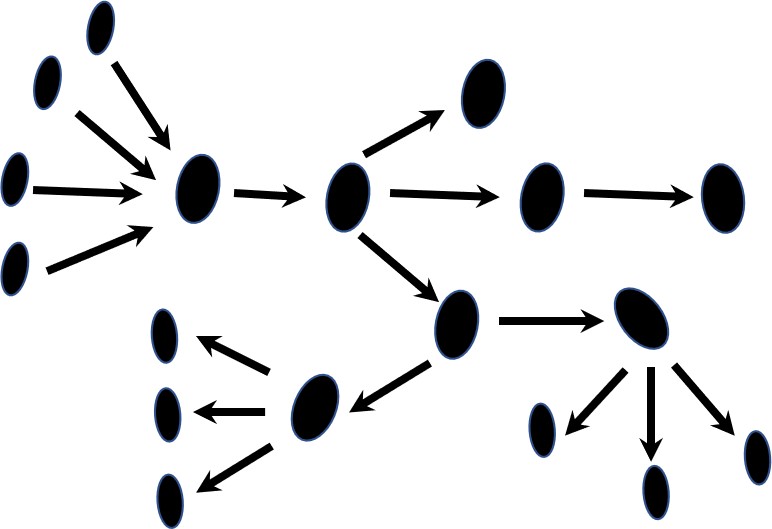

When it comes to supply chains, we have the capabilities to analyse and improve the flow processes of materials and merchandise. We are the experts in optimizing methods and in boosting the productivity of supply chain operations.

Before anything else, however, we need to upgrade our identity. We should stop calling ourselves Industrial Engineers. It’s too vague.

We should instead start calling ourselves Supply Chain Engineers. Just as with other engineering titles, we need to be recognized quickly for what we do by what we call ourselves.

Because supply chains are at the core of global business, it’s time we see ourselves as Supply Chain Engineers. We can build them, we can improve on them, and we can make them risk-averse and world class.

We have evolved and we should continue to do so. Industrial Engineer as a title belongs to a time when manufacturing was prominent. Today in the 21st century, supply chains are prominent. Whether it be in products or services, there will be supply chains. And we have the means, the skills, and the talent that earns us the title as Supply Chain Engineers.

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the vulnerability of supply chains. It also has demonstrated the potential value of our vocation as Supply Chain Engineers.

We have the ability to change the world for the better. We are Supply Chain Engineers. We can make supply chains resistant to present and future adversities and deliver world-class productivity to the enterprise.

We have the power and we have the responsibility to demonstrate that power.

Let’s show them what we got.

About Overtimers Anonymous