How do you want your supply chain relationships to be like?

Supply chain relationships consist of the connections between enterprises such as those between enterprises and their vendors, service providers, and customers. They also include the interactions between internal operating groups within enterprises, such as purchasing, inbound & outbound logistics, manufacturing, and planning.

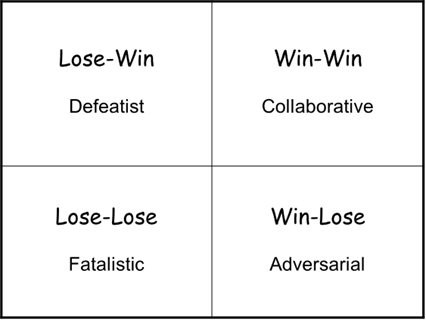

There are four types of supply chain relationships:

In Lose-Win, the other party benefits; the enterprise doesn’t. The ‘partner’ gets the better deal; the enterprise does not. The enterprise’s leadership adopts a defeatist mindset while its ‘partners’ dictate the conduct of the relationships. The enterprise finds it futile to wrangle for better terms. An example is when a larger multinational retailer lays down a take-it-or-leave-it approach to competing small businesses. The ‘winning’ small business firm adheres to the multinational’s terms & conditions even if the firm finds them unfavourable.

In Lose-Lose, the enterprise and its partners resign to a relationship that they see as necessary but hold no hope for benefits. An example is a courier service who loses money from shipping packages to a client’s customers who are in faraway rural places. The courier service shoulders high transport costs it cannot pass to its client because of government-regulated restrictions. Meanwhile, the firm’s order-to-delivery performance is below par because the courier firm will not give priority to transporting the firm’s products. Both parties incur losses as they pray their business environments would change someday.

In Win-Lose, the enterprise sees benefits only coming by having things done its way and not favourably for its partners. Winning can only come when the other side loses, much like in games of sports. Concessions from partners is the goal. An example is when a large fast-food corporation demanded a winner-take-all approach to its chicken suppliers. The fast-food executives insisted chicken suppliers allocate all their supply to the fast-food’s commissaries as well as preferential pricing which would be lower than the rates sold to competitors.

The ideal of any relationship is Win-Win, where the enterprise and its partners benefit from each other’s businesses. A tangible proof of a win-win relationship is a mutually beneficial contract, such as that between a service provider and a client. Exclusive dealerships, distributorships, and 3rd party outsourcing services are where we can find potential win-win relationships. Apple corporation’s long-time partnership with Taiwanese firm Foxconn is a close example of a win-win relationship.

Aiming for Win-Win relationships is the principle behind building supply chains. Whatever structures & systems the enterprise and its partners set up must support a Win-Win ideal.

Supply chains are not meant to have one or more losers among their relationships. A losing partner in a supply chain relationship will inevitably lead to losses in productivity and to higher risks.

The small business awarded a Lose-Win contract from a multinational retailer was reluctant to invest for further growth. It decided to seek other avenues to grow. The small business offered to distribute for other suppliers even if it violated its contract with the multinational. The multinational fired the small business but by then, it already had established more favourable agreements with other suppliers.

The transport firm & its client stuck in a Lose-Lose relationship decided to go their separate ways. The client firm discovered it could save costs by buying its own trucks to deliver products to customers in distant rural areas. The transport firm, meanwhile, refused to adapt its transportation to changing infrastructure; it eventually lost market share to upstart companies.

The fast-food corporation in the Win-Lose scenario was caught off-guard when its suppliers one day could not deliver needed quantities of chicken to its restaurant branches. Shortages ensued. The fast-food firm’s market share dropped as it suffered a public relations nightmare due to out-of-stock of its flagship chicken product. The fast-food firm was forced to shut down branches to wait for supply to catch up and was compelled to renegotiate its contracts with suppliers.

Apple’s Win-Win relationship with Foxconn is not perfect. Both had faced issues such as labour conditions and spikes in trade tariffs. Yet, both continued to collaborate in manufacturing & delivering new products of high quality to their global customers. Both had over their years of working together built a system & structure which strengthened their product supply chain. And both continue to find ways to improve.

It is in continual improvement where we justify the Win-Win relationship for enterprises in the supply chain. Relationships between individual enterprises enable the flow of merchandise. In a scenario where there’s at least one loser, productivity suffers and everyone loses.

In supply chains, relationships matter. When everyone wins, everyone benefits.