Sometimes identifying a problem is not in observing what’s going on; sometimes it’s noticing what’s not there.

In my blog, “Where are the Supply Chain Experts?”, written last March 2020, I wrote there were no supply chain experts seen working side by side with business and government leaders in solving supply issues at the height of the CoVID-19 pandemic.

As media reported issues regarding shortages of medical supplies and consumer goods, we heard no real solutions to the problems. And as government executives encountered obstacles deploying vaccines, there was no supply chain professional managing proper and efficient distribution.

There may have been much talk about supply chain issues but there was little in the way of supply chain solutions coming from supply chain experts.

Not that there aren’t any supply chain experts. There have been numerous podcasts, blogs, and testimonies on the subject but most if not all the supply chain professionals were really just broadcasting opinions. There wasn’t much in the way of seeing them together with leaders or the leaders even mentioning any of them at all.*

Simply put, despite the attention, nobody is putting weight in people with supply chain expertise. Hardly any supply chain professional is in the limelight, even as the global CoVID-19 has brought on the most traumatic economic disruption in history.

There are several reasons which I believe why we don’t see supply chain experts taking the lead in solving major supply chain problems:

Reason #1: Supply chain people are operations people and operations people are not expected to go out and interact with the outside world.

The paradigm of operations people is to focus on what’s going within the workplace, that is, they focus inward. Except to buy or deliver or hire a contractor, operations people don’t really interact with the outside world.

That essentially had been my upbringing in most of my supply chain jobs. I concentrated on my department, my workplace, the processes within that were assigned to me. Emphasis was always on what was going on within operations, not without.

Any interactions with the outside world were initiated mostly by people who were not in operations. Operations people did not initiate such things and I don’t think many do so up to today.

In other words, operations people, especially supply chain professionals, are proactive in what happens within the four (4) walls of factories, warehouses, and offices. We were not asked to improve the connections enterprises had with vendors, customers, and 3rd party providers. Executives emphasised performance measures, not relationships.

Reason #2: There aren’t many supply chain experts in the first place.

Many entrepreneurs are not supply chain professionals and many executives aren’t either.

That’s one reason maybe why we don’t see many chief supply chain officers. There aren’t that many experienced supply chain managers to begin with.

It’s not that the leaders don’t recognise the importance of supply chain management even to the extent of having it as an equal in the echelons of top management. It’s just that there are very few managers with supply chain experience.

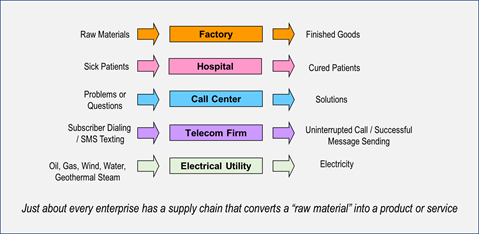

When I say experience, I don’t just mean experience in logistics or manufacturing. I mean experience as in synchronising operational functions and interacting with customers, vendors, and 3rd parties in procuring, transforming, and moving merchandise from one supply chain link to the next. How many people do we know have this kind of expertise? Chances are not a lot.

Reason #3: Supply Chain education is relatively new and not widespread.

Many people aren’t schooled in supply chain management. We can’t blame them for that; supply chain education is relatively new, as in it’s a course that only has been around since the 1990s, unlike finance and marketing which have been around for more than a century (longer perhaps). And supply chain management as a concept and application is still evolving.

Coupled with that are the ones who teach supply chain management. There aren’t that many supply chain teachers, at least one would call qualified to teach, or one who has experience in various supply chain activities.

Many supply chain courses teach specific subjects that tie in general operations management topics such as inventory management, production planning, transportation management, and operations research. The trouble is many of these courses don’t tie in the topics together to teach how the supply chain functions as a whole. They don’t offer the connectivity that illustrates how supply chain operations work together from end to end.

At the same time, supply chain education isn’t really uniform from place to place. Some schools link supply chains more to logistics while others stress transportation and purchasing. Some don’t even teach manufacturing’s connection to the supply chain, treating it separately even as it shouldn’t be. There’s really no formally standard course for supply chains as one would see for law, engineering, or business administration.

The people graduating from any supply chain management course from the 1990’s to the 2020’s aren’t therefore fully educated in supply chains. They’re just graduates taught with a hodgepodge of individual courses related to the subject, which in itself isn’t the same from one school to the next, from one teacher to another.

These make the diplomas and certificates some supply chain schools issue open to doubt. A certificate or diploma in supply chain management thus testifies to a school’s brand of teaching, not necessarily one that is generally applicable in any industry.

When it comes to bringing supply chain management to the forefront and developing it as a prominent field that addresses present-day issues via the three (3) aforementioned reasons, what should be done?

I believe education should be the starting point and the very first step should be to establish basic competency among candidates for the field.

I define basic competency in supply chain management as where one is familiar with operations, can at least see how to tie them in altogether towards overall optimal performance, and where one has the ability to plan, organise, direct, and control supply chains both in the day-to-day and strategic perspective.

Basic competency would be the foundation. Experiences afterward would be the building blocks that would develop the manager’s proficiency.

Both the education in basic competency and the experience one gains should not be inward looking but focused on the relationships and connections between parties and links within and outside the enterprise.

It would be a wholly new approach to some entering into the study of supply chains. But I believe it would be worth it. Many of the challenges we see in supply chains are precisely occurring in relationships and connections between functions and parties inside and outside enterprises.

Where can we find the teachers or just even the mentors? Because there are not many of them, many aspiring students would be left on their own to look for and put together the bits and pieces experiences would bring.

But even as they may be few, there are those who can at least help new managers attain that basic competency. I’d like to think I can be one of those teachers given the knowledge and insights I gained from close to 40 years’ experience in the field.

*[President Joseph Biden of the United States led a “summit on semiconductor and supply chain resilience” in April 2021 in which the President discussed with chief executive officers (CEOs) how to tackle supply issues particularly in semiconductor chips. No prominent supply chain expert was seen stepping up to address the issue].