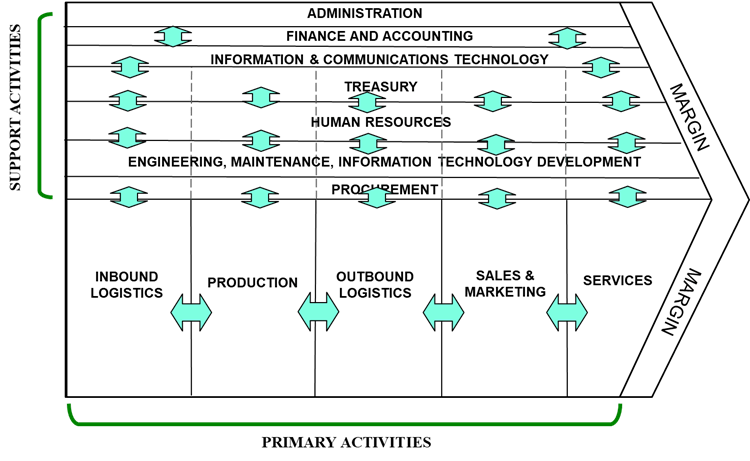

Michael Porter introduced the Value Chain model in his seminal book, Competitive Advantage,1 in 1985. The value chain broke down activities of the firm (the enterprise) and how they collectively contribute to the value of products & services.

How well activities perform and interrelate would manifest in the margins, which are the difference between value (what customers are willing to pay) and the cost to create that value.

The key words are ‘perform’ and ‘interrelate.’ How functions or departments perform and work together determine the value of the enterprise’s products & services.

It isn’t something new. Porter devised the value chain model in the 1980s and we have learned and improvised from the model since. The value chain brought to light the importance of our individual roles & responsibilities to the enterprise. At the same time, it emphasised interdependency in the organisation and between organisations.

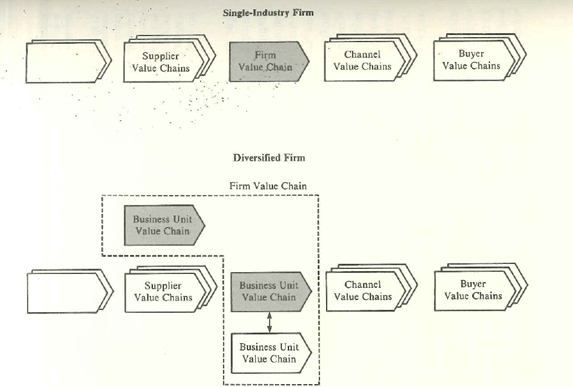

Michael Porter, however, also brought to our attention to the value system. He shared that value chains of enterprises are linked. We connect, for example, with the value chains of our vendors, our customers, our channels (e.g. distributors, dealers) and 3rd party service providers. We also interact with the value chains of our enterprise’s business units, such as with the other product lines of our business.

We are interdependent not only via the functions & departments within our enterprise but also with the enterprises we buy from, deliver to, engage for services, and share time, talent, & resources.

The value chains collectively put together as the value system influenced the margins of each chain’s products & services. Vendors and service providers impacted our enterprise’s margins as much as we impacted our customers.’ At the same time, our interactions with other business units also influenced their margins.

Michael Porter’s value chain and value system reinforced the supply chain model which we have come to espouse. Although value chains are broader in coverage and stress maximising margins via competitive strategy, both value chain & supply chain emphasise the importance of performance & relationships within and between enterprises.

Thanks to the value chain and supply chain, we have managed to develop & implement strategies that have brought our enterprises to new heights. Our businesses have grown in leaps and bounds as we have been able to competitively deliver our products & services to markets around the world. Via cutting edge innovative technologies and via aggressive organisational development & teambuilding, we have integrated our operations into networks of interdependent activities with the common goal of making available merchandise at the lowest cost and best service. As a result, many of our enterprises have accumulated greater wealth, gained better than expected competitive advantage, become better corporate citizens, and seen our businesses prosper beyond our wildest dreams.

The value chain and the supply chain are models that have revolutionised the way we manage our business operations.

Why, then, however, are we complaining about supply chains? Why are we pinpointing them as causes of chronic disruptions to our overall strategies? And why are we often saying there’s a supply chain crisis? What are we missing?

We can speculate that over the more than 40 years since the supply chain was introduced, we have run into the following wrong mindsets :

Wrong Mindset #1: We didn’t accept supply chains in the executive suite

The value chain is a model to illustrate how we can better manage our enterprises to gain competitive advantage via increased margins in our products & services. We have used it to persuade our people to perform and interact together towards an aligned strategy.

The supply chain is a model for operations management in which we integrate the activities underlying the flow of merchandise & services toward higher productivity and added value for our customers.

Many of us, however, don’t see supply chain management as a top-level responsibility. We didn’t see the validity of integrating key operations under one leader. Whereas we’d have maybe executive positions for manufacturing, quality, or purchasing, we hesitated or avoided granting one that would cover all the operations that were essential to the flow of products & services.

And for some of us who did establish supply chain management positions, we limited their scopes. We would give supply chain managers authority over some functions like procurement, planning, and logistics but would not give them any power over purchasing and manufacturing. We rationalised that supply chain management positions would cover too much ground or would be too powerful to tame.

We, instead, relegated supply chain management to the middle of management hierarchies. Middle-level managers mostly, and frequently informally, ended up handling the issues that arose in supply chains. Logistics supervisors constantly followed up manufacturing for finished products so that pending orders would be served, production managers sought raw & packing materials from the inbound materials department, and the inbound logistics people would fight with quality assurance inspectors to release just delivered but badly needed materials.

As more and more supply chains became global in scope, disruptions intensified to the point of alarming executives. New enterprise upstarts, fickle international trade laws, a worldwide pandemic, military conflicts, and politically based economic sanctions became too much for middle management to handle. We eventually embraced supply chain management into our enterprises’ board rooms and executive suites.

Wrong Mindset #2: We treated supply chains as a given, not something we can change

We supply chain managers finally got our seats on the executive and board room tables, but many of us still had preconceived notions of what supply chains are and how they are to be managed.

One common preconceived notion is that supply chains are a given. We work with what systems & structures are available and we don’t think of changing them. The existing production lines, the warehouses, the systems our people use, the transportation modes, the shipping ports, the vendors, and the 3rd party service providers are rigid. We don’t try to, or even think, of changing them for whatever illogical reasons, the number one of which is fear. We’re afraid we won’t find alternatives to what are already existing (e.g. international transport routes), we fear we’d be uprooting from locations (e.g. moving factories from places they’ve been for many years), or we just don’t want to face the resistance (e.g. labour unions refusing to consider automation).

The good news is that we can change supply chains. But it’s not only fear we’d have to overcome. We’d have to change another mindset in doing so.

Wrong Mindset #3: We believe we can improve supply chains by managing them.

We have employed supply chain management talent in the hopes that the new hires would effect significant changes that would mitigate risks and head off disruptions.

That’s not going to happen. Because supply chain managers work with what they have and don’t have the full-fledged expertise to change systems & structures.

An analogy is city traffic. In Manila, Philippines, where I live & work, traffic is a daily problem, if not crisis. City politicians and their police departments manage their respective traffic snarls by assigning enforcers at intersections, enacting ordinances (e.g. prohibiting cars on weekdays via their license plate numbers), revising road flow (e.g. making streets one-way instead of two-way), installing more traffic lights, and painting lines & putting up signs. In short, they manage traffic within existing the infrastructure of roads, traffic enforcement, public transport, & local politics.

Traffic management can do only so much, however. If the systems & structures remains the same, the traffic mess will continue. And in Manila, despite all the efforts of past decades, it has.

What’s needed to improve traffic in cities like Manila is not management but engineering. Managers manage what’s in the infrastructure; engineers change them. Engineers offer the problem-solving game-changing expertise that lead to new & better systems & structures. Manila’s traffic mess can only change when we design & build new road networks, reset & introduce new public transport systems, and overhaul & replace the governing hierarchy.

We can’t manage our problems towards solutions. But we can engineer solutions to our problems.

Michael Porter introduced the value chain in 1985 and it has helped to highlight the importance of supply chains in operations management. We have adopted both value chains and supply chains into our strategic portfolios, but we need to overcome wrong mindsets if we are to progress. These include the following fixes:

- Accepting supply chain management as an equal in the high-executive echelons of our organisations;

- Not treating supply chains as a given, but as an avenue for change;

- Engineering, not management, will bring that change.

In effect, for supply chain management to work, we’d need to bring in the engineering talent to solve our problems and head off future crises.

The sooner we accept that engineering can be a partner for management in solving our supply chain crises, the earlier we can get things done.

1Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage (New York, New York: The Free Press, 1985) pp. 33-61

2Ibid. Figure 2-2, p. 37 (arrows provided by writer of this essay)

3Ibid. Figure 2-1., p. 35