“No, we will not change our sales policy,” the general manager of the consumer goods wholesale trading company tersely said.

As I was formerly a logistics manager and land transportation service provider (trucker for short), the wholesaler GM was asking me for advice on how to bring down transportation costs, which had been rising sharply. And when I did give her my advice, she didn’t like it and replied with the answer above.

Transportation costs were one of the wholesaler’s largest expenses and before my conversation with the general manager, the wholesaler’s truckers had been demanding higher freight rates. Despite coordinated efforts & negotiations between the wholesaler’s logistics staff and their truckers, the truckers remained adamant for rate increases. The general manager was reluctant tp grant the increases but knew the risk if she didn’t; she couldn’t afford losing delivery capabilities as her wholesale business was growing.

I told the GM that one best and quick option to bring down freight expenses was to stop the month-end surges in sales orders.

The wholesaler had been offering incentives in which customers can avail of additional discounts when they bought more than PhP 1 million (approximately $USD 17,000) of merchandise within a calendar month. Sales employees also had monthly quotas tied in with customer orders. The more customers bought, the more bonuses the salespeople would be entitled to.

Because the wholesaler measured sales based on actual deliveries received, customers and sales raced to submit their orders to the wholesaler’s logistics department before the month-end deadline. Logistics staff, in turn, would work overtime to load & dispatch deliveries to reach customers’ doorsteps before the close of business of the month’s last day.

The number of delivery trips dispatched on the last week of a month was typically four times (4x) the number of trips dispatched on the first week of that same month. That meant truckers had to make available four times more trucking capacities on the last week versus the first week.

Truckers procured new trucks and subcontracted vehicles from third parties to augment their fleets such that the number of available trucks would be in lockstep with the wholesaler’s month-end order swings.

This led, however, to many of the truckers’ vehicles being idle on the first week of the month before they would be needed for the last week’s surge of orders. Truckers had to shoulder not only depreciation but also overhead expenses to maintain their vehicles on top of the thin profit margins they eked out from their subcontracting arrangements, even though their own vehicles weren’t being fully utilised.

Truckers, thus, factored in these expenses in their petitions for higher freight rates. The wholesaler’s general manager would argue in vain against the petitions but the truckers wouldn’t budge; the truckers weren’t making money.

When the general manager, therefore, sat down with me to ask what can be done to reduce her freight costs, I told her that she should study smoothening her month-end order surges. It was one thing to deliver versus orders triggered from incentives, it was another to fulfil demand based on actual consumption. It was obvious that the wholesaler was doing more of the former than the latter.

It had been proven that consumers buy based on what they need, and don’t wait till the end of the month to do so. Consumer demand does not skew toward the end of every month, even though they may speculate every now and then. Without incentives, the wholesaler’s customers would buy products closer to consumers’ buying patterns which would likely be steadier and more consistent week to week. Exceptions would be introduction of new products or whenever there were price changes.

If the wholesaler’s customer orders arrived in steady quantities than in swings, truckers would be able to utilise more of their existing fleet capacities as their trucks would be delivering more or less the same number of trips per week rather than a skewed few-to-many trips from the month’s first week to the last. Trucks wouldn’t be standing by idly at the start of the month and they would have less need to subcontract from third parties. The wholesaler would have more leverage to maintain, if not reduce, freight rates as truckers would reap more productivity from their operations.

But the wholesaler general manager didn’t want a solution that would disrupt her company’s current sales scheme. She feared that letting go of incentives would mean lower sales volumes as well as risk losing competitive advantage from rivals (who also did sales incentives).

She abruptly ended discussion on the matter after she tersely replied in the negative to my advice. With that, I just said “okay.” I packed up, bid farewell, and left.

The wholesaler continued to be successful financially and as a market leader. It continued to grow as prospects for its future remained bright.

But would the wholesaler’s business have been more better off had the general manager at least considered the idea of ending month-end surges? Maybe yes, maybe no. One thing we can be sure of is that productivity of the wholesaler’s operations could have improved. But apparently, the wholesaler’s general manager didn’t really put much importance to her operations’ productivity.

The lack of putting importance into supply chain productivity is common in many enterprises.

The president of an exclusive distributor of an information technology corporation’s product line of desktop printers, components, and supplies also had a similarly blunt reply when I advised he should re-examine his sales strategy which were causing sales order surges every month. “There’s nothing we can do about it,” he responded, as tersely as the wholesaler’s GM said a few years earlier.

“How many people buy printers only at the last week of the month?” I asked. But the president would hear no more.

Sacrificing supply chain productivity to spur sales every calendar month is a symptom of a mindset in which sales & marketing schemes reign supreme in many enterprises’ strategic plans.

My stories of the wholesaler GM and the IT distributor’s president echo with others I was asked for similar advice. From a snack foods corporation, a roof tile manufacturer, a metals importer, a food condiments producer, to multinational consumer goods conglomerates and even an energy utility company, many enterprises adopted strategies centred on short-term sales growths. Supply chain managers were expected to deliver versus revenue and financial goals rather than improve the productivities of their operations.

What exactly do I advise enterprises? Plan not only for demand creation but also for demand fulfilment. A business is basically about doing both. Maybe a business can still grow by creating demand exponentially and fulfilling demand unproductively, especially if competitors are also doing the same. But we can only imagine what potential breakthrough opportunities could be had if enterprises focused on both the creation and fulfilment of demand in their strategic plans.

The following is an example of how a company benefits when it embraces supply chain productivity into its strategic planning:

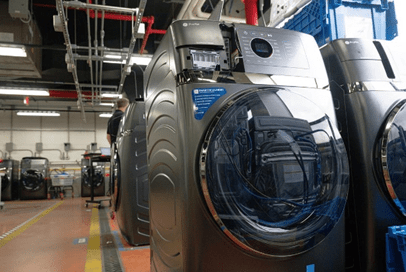

PHOTO: JON CHERRY FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

–Paul Page, Resetting Supply Chains, The Logistics Report, 03 July 2024, The Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

It can be done.