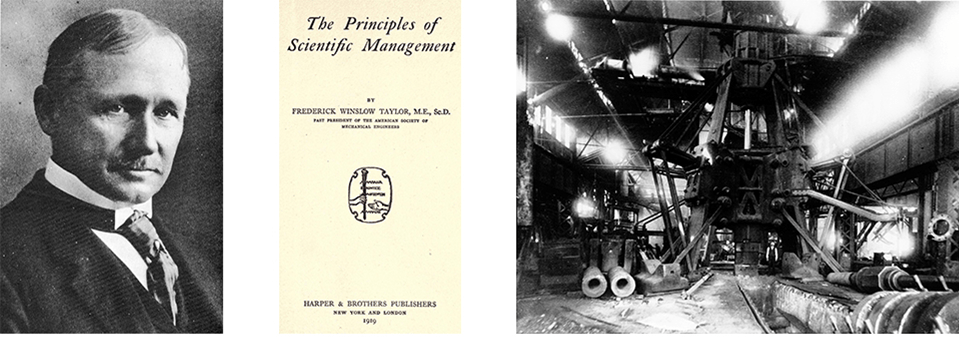

In March of 1911, Frederick Winslow Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management debuted to the public. It was the height of the Industrial Revolution in the United States of America. Corporations were mass producing items and many Americans were employed in factories. Mr. Taylor’s Principles couldn’t have come at a better time as when it did, it revolutionised the ways of management.

The Principles of Scientific Management argued for the necessity of efficiency in the workplace. Without efficiency, there would be no prosperity. Employees, especially those in factories, had to be productive if enterprises were to be prosperous. Taylor defined prosperity, or more fully “maximum prosperity,” as not only “large dividends” but “the development of every branch of the business to its highest state of excellence, so that the prosperity may be permanent.” A business is prosperous when the workers are productive.

With that in mind, Taylor proceeded with the four (4) elements which comprised the Principles of Scientific Management:

- “…develop a science for each element of a man’s work, which replaces the old rule -of thumb method;

- “…scientifically select and then train, teach, and develop the workman;

- “…heartily cooperate with the men so as to insure all of the work being done in accordance with the principles of the science which has been developed;

- “There is an almost equal division of the work and the responsibility between the management and the workmen.”

The Principles of Scientific Management stressed objectivity in job performance and in how we hire & train people but encouraged cooperation & recognition between managers & workers using science as a common ground.

Although Taylor encountered criticism for giving the impression that workers were nothing more than machines meant to be tinkered & optimised, industries adopted his Principles and drove a cultural shift in how we manage our organisations. As a result, over the next hundred years, we became more efficient and more productive.

We have evolved from the Principles. We no longer use the term “scientific management,” but we rationalise our management methods with terms like “evidence management,” “big data,” “statistics,” and “data analytics.” We apply “automation,” “lean thinking,” and in the 1st quarter of the 21st century, we have become enthralled with “Industry 4.0,” and “artificial intelligence.” If we think about it, all these terms, phrases, & buzzwords directly or indirectly emanate from Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management. Whether we like it or not, we are purveyors of what Taylor promoted for the progress of productivity.

The Principles of Scientific Management spawned Industrial Engineering and Operations Management. Industrial Engineers defined themselves as designers, developers, & builders of manufacturing systems & operations structures with the purpose of optimising productivity of workers together with their equipment. Operations Management, on the other hand, rose as “the administration of business practices to create the highest level of efficiency possible within an organization. It is concerned with converting materials and labour into goods and services as efficiently as possible to maximize the profit of an organization.” Industrial Engineers stressed they are engineers while Operations Managers emphasised their roles as administrators of the activities essential to the value of their organisations’ products & services.

But as IEs and OMs debate about their identities, those of us who are business leaders see both as change agents for improvement. At work, we don’t split the difference between the two. We only care that IEs & OMs optimise our operations as well as continually improve them.

But the time has arrived that we should perhaps make the distinction between what is management and what is engineering.

In 2023, the world was emerging from a global pandemic, the worst global disruption since the Second World War. Supply chain management had suddenly become popular thanks to product shortages & service failures in which the pandemic impacted the flow of merchandise from sources to end-users. Business leaders recognised supply chain management as a strategic pillar alongside marketing, finance, and people. The supply chain had become a high-profile priority of organisations.

We catapulted the supply chain to the top of our enterprise agenda because we could no longer relegate it to middle-level operations management. We realised that supply chain management is not only about multi-operation integration & multi-enterprise collaboration but also about strategic interdependent interaction with functions such as marketing, finance, and human resources.

Supply Chain Management is rooted in Operations Management. It is a discipline that concerns itself with the operations that underlie the relationships that run between vendors, operators, quality control inspectors, logisticians, transporters, service providers, labourers, & customers.

Industrial Engineers, however, also do a lot of work with supply chains. Supply chains are obvious parts of the IE’s scope in the improvement of productivity. Despite whatever perception that Industrial Engineering leans toward management, IEs are engineers who focus on improvements in systems & structures, like those that underlie supply chains.

Frederick Taylor was a mechanical engineer. He saw a need to improve workplace efficiency and applied his engineering background to do so. The big challenge was to somehow standardise the work of human beings, given that we as individuals each have different physical make-ups.

But he attempted anyway, and it resulted in workplace standards that were applied first to factories and then to other areas of industry, such as warehouses, hospitals, and transportation. His pioneering work in establishing standards in time & motion efficiencies led to his publishing of the Principles of Scientific Management, and the birth of Industrial Engineering.

I’ve heard critics say, however, that there is too much subjectivity in Industrial Engineering. IE seems more based on empirical mathematics, in which IE seems to be more reliant on experience than on proven scientific theory. Industrial Engineering methods also are seen as more art than science, less objective than what we would be in other engineering disciplines.

Hence, some people say IE is not engineering. It’s management that combines with engineering. It doesn’t help that some universities offer IE with course titles such as “Industrial & Management Engineering,” or just “Management Engineering.”

In my mind, Management Engineering, Engineering Management, Industrial & Management Engineering are oxymorons. An oxymoron is “a rhetorical figure in which incongruous or contradictory terms are combined.” To put it simply, engineering is not management, and management is not engineering. Putting together both as one term is a futile and silly attempt to mix one with the other. Each are different from one another as apples are from oranges.

Inspired from Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management, Industrial Engineers started out as efficiency experts targeting workers to be more productive with their time. IE, over the years, diverged from the basics of time & motion to expand to areas such as ergonomics, statistical quality control, facilities planning, and queuing theory. As much as they influence management, IE is a field that isn’t management. It is engineering that designs, develops, & installs systems & structures with the purpose of improving productivity, never mind if the math IEs use are more empirical than theoretical.

Supply Chain Engineering stems from IE. It expands from improvement of the individual workers’ relationships with their workplaces to groups of workers’ relationships within & between operations. It derives from the applications of IE in which it focuses more on the optimal flow of merchandise & services from their sources to their ends.

Whereas IEs are challenged to standardise solutions for individual humans in their workplaces, Supply Chain Engineers are challenged to standardise solutions for individual group operations and their links to others.

The mathematics of SCE is therefore just as daunting, if not more, than it is for IE. For as much as IEs work to optimise the productivities of individuals, SCEs attempt to optimise the productivities of supply chain operations.

Many supply chains in the present day are inefficient and offer plenty of room for productivity improvement. We can see these deficiencies or imbalances everywhere. Port facilities are either too slow, too overloaded, or are frequently underutilised. Transportation, whether land, sea, or air, often experience constant uncertainties in lead times. Storage facilities either have too much stock or are lacking in stock. Factories either have too much excess manufacturing capacity or don’t have enough to keep up with demand.

We can no longer expect supply chain managers, as operations managers, to improve our organisations’ systems & structures on top of ensuring the continuous flow of merchandise & services. We as supply chain managers can’t pursue needed changes by ourselves.

Engineering is not management, and we can’t do both as supply chain managers. Frederick Taylor promoted science into how we manage our enterprises. And more than a hundred years later, we face challenges to apply science in the continuous improvement of our supply chains. To do that, we must partner with engineers to help us make those productive changes. Engineers have the education and expertise to help us make that happen.

We must realise that we can no longer manage supply chains to make them better.

We need to engineer them.

One thought on “The Science Behind Management & Why We Need Engineering”