I looked at the bottom of a dog food can at the pet shop to check its expiration date. It said “10/26/2026,” but the production date said “10/27/2023.” I concluded the dog food was safe as I bought the can of dog food on May 25, 2024.

I thought, however: why was the production date more than six (6) months ago? Why did it take so long for the product to be purchased by me, the consumer, from the time it was canned at its factory?

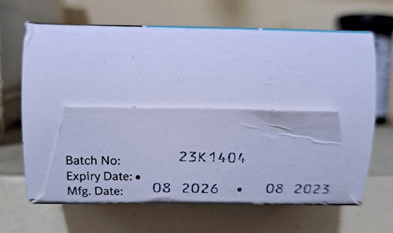

We see the same discrepancy in dates not only in canned pet food but in other products as well. Pharmaceutical prescription tablets I bought on May 02, 2024, show an expiry date on August 2026 but a manufacturing date of August 2023. Why did it take nine (9) months from the time the tablets were packaged to when I bought it from the pharmacy?

Time study after time study has shown it doesn’t take more than a week to make most products from scratch. Items like my prescription medicine and dog food don’t take more than a day to pack or can. Why then does it take so long for merchandise to move along supply chains?

Process flow charts have revealed that merchandise spend a lot of time in inventory, either in storage or in transit, i.e., inside vehicles like container vans on ships.

Is it worth the time and effort to shorten the period from when a product is created to when a customer buys it?

For products like newspapers and perishable food, the first thing that comes to mind is yes. Newspapers published more than a day ago or fruits harvested more than weeks ago don’t sell; hardly anyone buys to read yesterday’s news or eat over-ripe fruits.

It also makes sense to not have products languish in inventory when customers clamour for them. Aircraft manufacturers and shipbuilders, for example, don’t hesitate to deliver their finished planes & ships to impatient customers who usually wait for years for their orders.

Enterprises that customise items logically avoid keeping products in stock. Tailors tell their clients to pick up and pay for their bespoke suits when they’re done. Some bake shops penalise customers who order but are late in picking up their cakes.

For those of us who sell mass-market items like consumer goods, we opt to keep inventory equivalent to several days of sales, which can be either based on historical or forecasted demand. The stock levels we keep depend on how expensive the product is and how regular customers buy them. The more expensive the product (e.g., luxury wristwatches), the more reluctant we are to tie up our cash in inventory for long periods of time. The more predictable our products sell (e.g,, multivitamins), however, motivates us to keep more stock of them.

We do not stock items which experience erratic demand. We make-to-stock items that move frequently or steadily. We make-to-order items which customers don’t purchase often, or which differ in specifications or requirements from one buyer to the next.

The risk of keeping low stock levels is we may not have enough items immediately available to sell. Customers don’t go to supermarkets to wait for groceries to arrive. Customers want their items now, otherwise they’ll go somewhere else or buy other items.

This hasn’t stopped us from counting on customers to wait anyway. Customers who like our products may prefer to wait rather than buy items from rivals. They’ll also wait if they have no other choice (we can’t easily find alternatives to supply our electricity & water, for example).

We keep inventories to buffer against demand variations which we don’t expect or can’t forecast accurately. We try to keep enough items to serve customers as soon as they want them as much as we try to not to keep stock that would end up idle for months or worse, unsaleable due to obsolescence, degradation, or damage.

Managing inventories is as much an active endeavour as it is for managing purchasing, manufacturing, and logistics activities. We plan, organise, direct, and control inventories as much as we do the operations of procurement, inbound & outbound logistics, and production. We minimise the time it takes to make items as much as we strive to reduce the quantities of items that sit in our warehouses.

So, why then does it take so long for items to flow from production to customers if we are already working hard to optimise our operations & inventories?

Many of us would have different answers to that question and we would rationalise them depending on the industries our products are in. Here are some of them:

Answer #1: Time adds up from one inventory location to the next

As items move from one location to another, they accumulate time waiting in one storage facility to the next. The total time adds to the length of time from production to when the customer buys the item.

Some items also undergo quality inspections & sampling testing at different locations and are therefore intentionally put on hold until they are cleared or certified. This adds more time to a product flowing through the supply chain.

Answer #2: Items wait for orders before they’re served

Many manufacturers wait for middlemen like dealers or distributors to order products before they are shipped. If dealers or distributors don’t order, items sit in inventory and wait.

Answer #3: The time to transport can be long

If products are coming from far off places, the time to transport them would add to an item’s production-to-customer journey. If products are passing through international gateways, there would be additional time spent for customs inspections & clearances and perhaps for other government requirements.

Given the answers mentioned above, a product would take some significant time from when a factory makes it to when it reaches buying customers.

But as much as supply chain managers may offer answers such as these, should we just accept that it takes as long as six (6) months for products like canned god food and prescription medicines to reach customers from the manufacturing lines?

Some executives would just say ‘yes,’ and that would be that.

Many supply chain managers focus a great deal on activities within the enterprises which employ us. We don’t manage entire supply chains but those that lie within the borders of the businesses we work in.

Hence, we optimise the operations of our employers, but we don’t optimise the supply chain flows upstream or downstream from where we’re at. Whatever productivity improvements we implement are mainly for the interests of our organisations.

We, therefore, would not concern ourselves about products taking too long to flow from production to customers, at least unless it becomes relevant to our business or jobs.

At the height of the coronavirus pandemic from 2020 to 2022, many customers took to social media to complain about orders taking so long to be delivered. Orders for computer chips, exercise gym equipment, medical personal protection gear, frozen meat, and groceries were taking so long to deliver.

Answers from supply chain managers, like those enumerated above, did not placate irate & impatient customers.

The outcries from many customers were loud enough for not only enterprise executives but also government leaders to seek action. Meetings were held. Quick-fix measures were applied.

Supply chain managers pushed vendors, manufacturers, and transport providers to speed things up. Demand shifted as some customers gave up or found alternatives. The problem faded but it wasn’t solved, if not even defined in the first place.

Asking questions like ‘why does it take so long for a product to reach customers after it’s manufactured?’ leads us to see how our enterprise’s operations relate with others in a supply chain we are participants in. It gives us an opening to know what our relationships are like with vendors & customers who are upstream and downstream from where our enterprises are.

It also forces us to evaluate the productivity of the entire supply chain. We may be productive in our operations but is the supply chain outside our enterprises’ scopes benefiting from our productivity?

Customers don’t care about what cause delays in deliveries; what they care about is getting the items they ordered and paid for. Hence, the onus is on us, the supply chain managers, to fix the flow of goods from procurement, production, logistics, to delivery to fulfil the demands of our customers.

We need to recognise that our jobs aren’t limited to within the boundaries of our operations but also includes our relationships at least with our vendors, service providers, and customers. What we do productively for our enterprises, we should ensure it contributes to the productivity of the supply chain; otherwise, our products, for what it may have been worth when we shipped it, would lose value to the final end-users.

Solving supply chain problems begins by asking questions and then getting stakeholders to enrol into identifying, defining, and working on solving the problems together.