Vendors selling to a manufacturing company were really angry, a newly hired purchasing supervisor discovered on her first week on the job. They complained that their bills weren’t paid for months after they delivered materials or parts. At the same time, supervisors from other company departments were voicing complaints that their purchase orders (PO’s) hadn’t been processed for many weeks.

Upon inquiry, the company’s accountants told the purchasing supervisor there weren’t any pending long unpaid bills on their records. The supervisor also checked her computer and found no pending PO’s to be filled, other than what she already received since her hiring date.

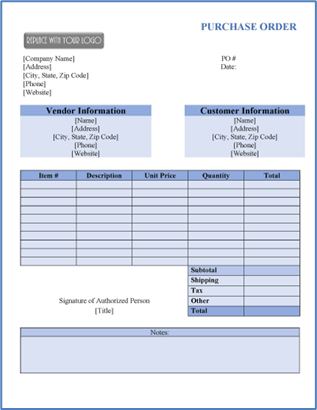

The supervisor checked the purchasing computer and saw that there were missing PO numbers. She made a thorough search of the purchasing office and discovered two boxes of PO’s that were underneath a desk of a former employee. The PO’s, which were unsorted and dated up to two years before, consisted of undelivered PO’s and PO’s that already were fulfilled but were left unpaid and unrecorded in the company’s accounts payables.

When the purchasing supervisor reported the discovery to the company’s finance manager, an audit was done which showed the company had staggering debts to vendors. The company couldn’t outright afford to pay the debts at once.

Angry vendors blacklisted the manufacturing company and refused to sell to the company unless the company paid cash for new purchases. Because of tight cashflow, the company could only buy materials in small quantities. Delays in inbound deliveries caused shortages and disruptions at the manufacturing company’s production lines which resulted in late deliveries to customers, who in turn stopped buying the company’s products.

This is a true story and a sad one. But it didn’t have a hopeless ending. The manufacturing company eventually settled its bills although the company’s purchasing department had to rebuild relationships with its vendors.

In many accounting systems, PO’s that are yet to be delivered by vendors or PO’s that have not yet been submitted to the accounting department are not yet considered payables and are therefore not yet included in financial reports. This would distort financial statement reports and hinder management of cashflow.

PO’s are therefore a blind spot in organizations. As operations managers request and seek approval for them, they are not visible as liabilities. This can create sudden problems for companies just as what happened to the manufacturing company mentioned above.

Internal audits would catch this problem but only if or when audits are done. Absent a visible purchasing management system, managers wouldn’t be seeing the status of PO’s. This lack of visibility of PO’s can upset a firm’s budget and financial strategy.

An energy company allocates a sizable budget for maintenance every fiscal year. The company’s engineers submit PO’s to requisition spare parts or to contract services for repairs and maintenance of equipment and buildings.

The engineers, however, tend to submit most of their PO’s towards the last quarter of the year to use up any of their unspent budgets. The end-of-the-year rush of PO’s would spike spending, push payables up, and cause a drain in cash-flow. As some PO’s are submitted at the last few days of the final month of the fiscal year, a good number of purchase order liabilities would lapse into the succeeding year which would disrupt financial cash-flow forecasts.

The management of PO’s depends a great deal on the purchasing manager. Purchasing managers are responsible for instilling discipline in how PO’s are processed from requisition to bidding to negotiation to fulfilment.

But interestingly, there isn’t much discussion about how to manage PO’s. When it comes to purchasing, more of what are talked about are collaboration and negotiation. Purchase orders belong to a basic system that doesn’t receive much recognition.

In some companies, requisitioners for materials, parts, and services sometimes bypass the purchasing department and order directly from vendors. When asked, their reasons from range from “I need the parts urgently” to “purchasing is too slow.” When it becomes normal for employees to buy directly, purchasing departments are left just processing orders and payments. Costs can run sky high as buying becomes uncontrollable.

A basic PO system simply needs clear policies, procedures and enforcement to set standards to function well and contribute to a company’s budget and cashflow strategy.

It starts with visibility and that means regularly updating the purchase order database and periodically reviewing reports. It continues with consistently acting on requisitions and moving the PO’s through bids, negotiations, and fulfilment in a manner that is timely and on target to pre-set performance standards. Direct purchases should be avoided, if not prohibited.

Just ensuring PO’s don’t remain pending too long and that they are processed for payment in a timely manner can be a big help in improving reliabilities of supplier deliveries, not to mention maintaining mutually beneficial relationships with vendors.

Actively managing the quantities, payment terms, and the timing of PO’s in coordination with requisitioners can make a big difference in managing working capital. Finance managers shouldn’t worry about spikes in procurements.

Purchasing is not just about bidding and negotiating for better value. It is also about how purchases themselves are managed within the confines of an enterprise’s internal supply chain. There is no dispute that purchasing’s key role is ensuring what is bought shall deliver the best value to an organization. One just should not forget the value of the system that governs the buying itself.